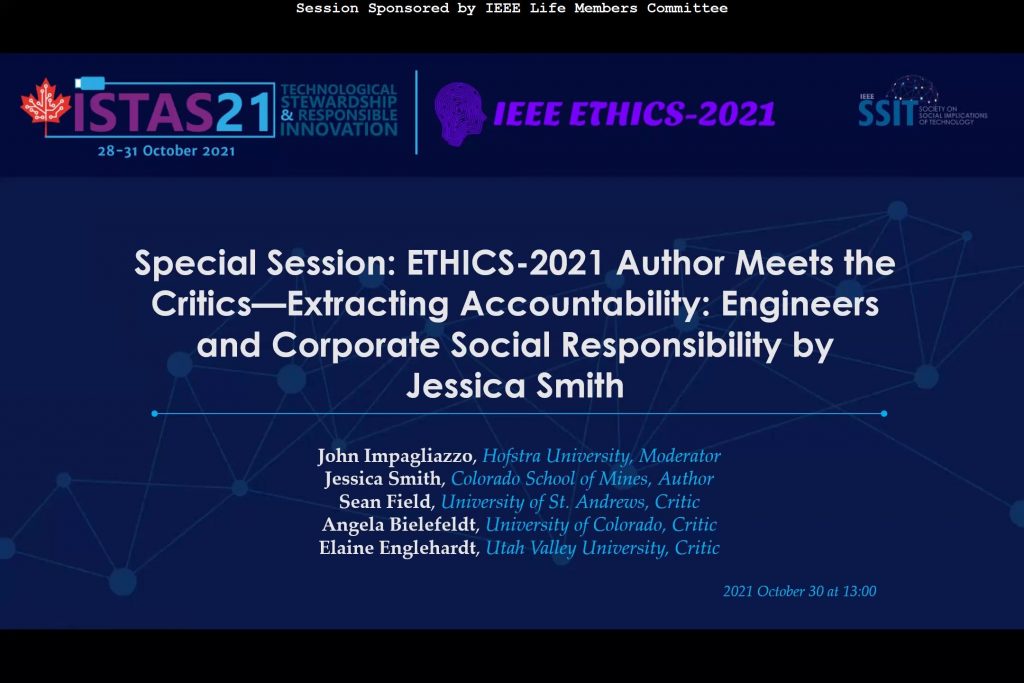

Extracting Accountability: Engineers and Corporate Social Responsibility, by Jessica Smith, investigates how the public accountability of corporations emerges from the everyday practices of the engineers who work for them. This Special Session took place during ETHICS 2021 on 30 October 2021. Moderator: John Impagliazzo

Click here to watch the video recording.

This Author-Meets-Critics panel featured Drs. Field, Bielefeldt, and Englehardt who serve as critics and respondents to Dr. Smith’s new book, Extracting Accountability: Engineers and Corporate Social Responsibility. The book explores the role of engineers in the mining, oil, and gas industries, and how they attempt to balance their professional obligations and their responsibilities to the public.

In his segment, Field began by noting Smith’s observation of ethnography as an exercise in human empathy that hinges on intimacy and trusts that cultural critique or anthropology (Smith’s academic background) often damages. Field observed that Smith “maintains a delicate balance of interlocutors’ perspectives and practices, giv[ing] them space to articulate their own experiences” with her goal being to “understand the accountability of technoscience corporations and the agencies of the people who constitute them.” In her book, Smith reveals that interlocutors found themselves trying to reconcile contradictions within various domains of accountability, as they are simultaneously demanded by their roles to be loyal corporate agents and guardians of public safety. Importantly, Field noted here the interlocutors’ interchangeable uses of ‘accountability’ and ‘responsibility’, probing the distinction between the two. Smith acknowledged this slippage and revealed that there is no universal definition for them that engineers adhere to. Field closed by asking what the racial dimensions were of the interlocutors in the industry, to which Smith later answered, “90% white”, signaling a limitation in her research regarding race.

Bielefeldt then took over, praising Smith’s incorporation of a challenge that all engineers face: the question of doing engineering well versus whether it should be done at all. Bielefeldt noted the book’s focus on agency and responsibility, and specifically the conflicting relationship of engineers to responsibility, as engineers seem to want more agency, but not necessarily the responsibility that comes with it. Though Smith says that engineers operate under a code of ethics that sets them up for multiple accountabilities, Bielefeldt refuted this point, saying that the code of ethics is a moving target and that it doesn’t unpack the way the health, safety, and welfare of multiple publics must be addressed. Finally, Bielefeldt reiterated the siloed nature of engineering in higher education, stating that the issue was one of attitude: “the promotion of the sense that engineers benefit the world” when they, in the same vein, caused problems they didn’t anticipate. Smith confirmed the existence of this attitude saying that the dangers include conflicting ideas between engineers, corporations, and interlocutors as to what they consider ‘public welfare’.

Englehardt finished up the critics’ portion of the panel by highlighting that perhaps engineering students did not want to know all the extra details surrounding social responsibility and engineering. She mused: “how long will their [minimal] training [on CSR] last with [engineers]? Can it become a habit, or will it leave after a few months on the job?” She then concluded with piercing questions about whether or not small towns discuss CSR and the license to operate with engineers, whether it’s in engineers’ economic interests to deny climate change, and whether such licenses can thus be granted by engineers with integrity.

Smith concluded the session by pointing to the necessity of interdisciplinarity in engineering education. She argued that it is important to change the current culture of engineering so that students are empowered to think beyond the scope of engineering and consider the social implications of their work, even if that means giving up their spot at the table to recognize someone else’s expertise in ethics education.v

JOIN SSIT

JOIN SSIT