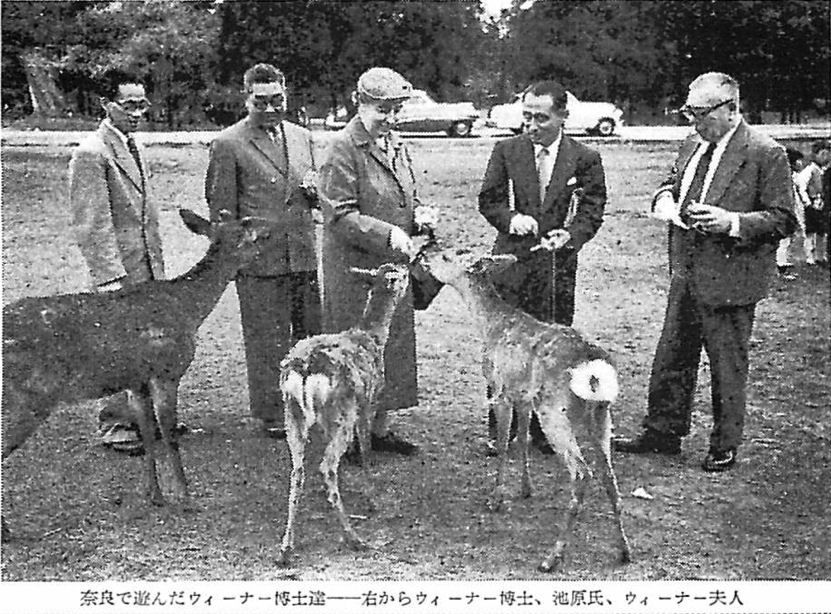

The Wieners playing in Nara. From the right: Dr. Wiener, Mr. Ikehara, Mrs. Wiener.

The Wieners playing in Nara. From the right: Dr. Wiener, Mr. Ikehara, Mrs. Wiener. Introducing a New Archive

At IEEE-SSIT’s July 2016 conference on “Norbert Wiener in the 21st Century: Thinking Machines in the Physical World,” presenters from a variety of disciplines offered their thoughts on the diverse intellectual and cultural lineages that link Wiener’s work — and early cybernetics more broadly — to contemporary issues in technology studies. Topics spanned contexts ranging from engineering, physics, and biology to sociology, political science, and cultural studies. And, thanks to an unexpected and serendipitous connection with Osamu Hirota (soon-to-retire professor and director of the Quantum ITC Research Institute at Tokyo’s Tamagawa University), a previously unseen archive of material added a new historical dimension to our discussions. What I am calling “The Ikehara Collection” shows us one of cybernetics’ previously under-explored paths of influence: into the world of Japanese physics and information technology. It opens up exciting new possibilities for understanding how Wiener’s ideas have promulgated around the globe into the present.

Figure 1. Shikao Ikehara portrait.

Figure 2. Ikehara Genius headline. Translation: Overwhelming World-Class Genius – Unnamed Young Man Discovered Simplifying Difficult Mathematical Proofs. “Ikehara Theorem” is Shining. [photo caption] Shikao Ikehara. (Asahi Newspaper, 31 October 1934) (trans. Shiro Uesigi).

Wiener visited Japan twice over the decades following Ikehara’s return to the country. The first trip was a short stay of about 10 days in the summer of 1935 when Wiener was en route with his family to take up a year-long fellowship at the National Tsing Hua University in Peiping, China (see Figure 3 and Figure 4). The second was a two-month lecture tour during the spring of 1956, when he was invited by the Japanese government-controlled broadcasting organization NHK and a group of nine different science and technology institutes (see Figure 5). Ikehara collected and saved a vast archive of documents pertaining to these two trips. When he passed away in 1984, he entrusted the letters, postcards, newspaper articles, magazine clippings, and photographs that made up this collection to his final graduate student, Hirota. Because Hirota believes that “these documents are historically important and very valuable to open to the public,” he has made a small preview available, first to attendees at the Melbourne conference and now also to readers of this publication. The eventual plan is to donate the full collection to the M.I.T. archives. The initial set of documents comprises a variety of genres: typed and handwritten correspondence from Wiener about both trips, Japanese newspaper articles and photographs covering details about the 1956 lecture tour, and media reflections on Wiener’s life and work that were published after his death in 1964 (see Figure 11).

Figure 3. Letter, May 16, 1935.

Figure 4. Note, June 16, 1935.

Figure 5. Dr. Wiener and cybernetics article. Translation: Dr Wiener and Cybernetics. By Shikao Ikehara. (trans. Nic Newby) . At NHK, in an effort to promote international scholarly discourse as well as to contribute to the improvement of our country’s scientific knowledge in general, we have decided along with members of the Nine Societies such as the Institute of Electrical Engineers to co-host the famous advocate of a new science, “Cybernetics,” Dr. Norbert Wiener from the United States. Dr. Wiener will arrive in Japan in April and stay until the end of May; during that time, in addition to being broadcast on NHK television and radio, he will be giving lectures on “Automation Theory,” “Information Theory,” and “Brainwave Theory” around the country at the following locations. April 17 (Tues) Tokyo / April 24 (Tues) Osaka / May 1 (Tues) Hiroshima / May 12 (Sat) Sapporo / May 21 (Sat) Nagoya / May 28 (Sat) Kyoto / May 4 (Fri) Fukuoka / May 17 (Thurs) Sendai.

As a whole, the Ikehara Collection offers a significant addition to the Wiener papers, in terms of 1) what it shows us about Wiener’s experiences in and relationship to Japan, and 2) how it opens up broader questions about archives and historiography. At the most basic level. this archive will be of interest to anyone who wants to get a glimpse into a previously unknown chapter of Wiener’s biography. He sent delightfully gushing letters to Ikehara both before and after his trips (see Figures 6–8), and the headlines of several Japanese newspaper articles — including one rather humorous phrase pointing out how Wiener and his wife have been “Smacking (their) Lips Over Tempura” (see Figure 9) — offer insight into the day-to-day activities of the mathematician’s travel schedule. We also get to see how the Japanese press presented Wiener and his ideas to their readers. Papers printed extended summaries of the basic “helmsman” metaphor at the root of the cybernetics project (see Figure 10) and anecdotes about his discussions with high-ranking industry figures (like the president of Nozawa Asbestos) about the implications of automation for issues of labor and unemployment (see Figure 9). They also offered more troubling comments about Wiener’s Jewish heritage and how his discovery of it somehow meant that he “had to … make an effort to grow into a whole being” (see Figure 10).

Figure 6. Post-trip postcard.

Figure 7. Post-trip Peiping letter.

Figure 8.Post 1956 trip letter.

Figure 9. Translation: Dr Wiener and Cybernetics. By Shikao Ikehara. (trans. Nic Newby). At NHK, in an effort to promote international scholarly discourse as well as to contribute to the improvement of our country’s scientific knowledge in general, we have decided along with members of the Nine Societies such as the Institute of Electrical Engineers to co-host the famous advocate of a new science, “Cybernetics,” Dr. Norbert Wiener from the United States. Dr. Wiener will arrive in Japan in April and stay until the end of May; during that time, in addition to being broadcast on NHK television and radio, he will be giving lectures on “Automation Theory,” “Information Theory,” and “Brainwave Theory” around the country at the following locations. April 17 (Tues) Tokyo / April 24 (Tues) Osaka / May 1 (Tues) Hiroshima / May 12 (Sat) Sapporo / May 21 (Sat) Nagoya / May 28 (Sat) Kyoto / May 4 (Fri) Fukuoka / May 17 (Thurs) Sendai

Figure 10. Creator of artificial brain. Translation: Creator of the “Artificial Brain.” Dr. Wiener in Japan. By Shikao Ikehara. (trans. Nic Newby). [photo caption] Dr Wiener. Starting on April 6th, the American mathematician Dr. Norbert Wiener will be visiting Japan and lecturing in various places over the course of the two months of April and May. The subject will be a new discipline proposed by the professor called “Cybernetics.” This word comes from the Greek κυβερνήτης [kybernetes] (helmsman), thus the study of taking the helm, or in other words the science of control. When taking the helm of a ship, in order to move the helm one must give orders. Moreover, to make the helm follow one’s will, one must send information to the helm to control it. The type of control and communication involved in this operation are matters that can apply to both machines and animals. If you think about our daily lives, you will notice that our bodies are taking in extremely nuanced information and self-adjusting based on that information. For example, if you somewhere that is hot, you sweat to prevent your body temperature from rising; when you are cold, information is transmitted through the nervous system to prevent the body temperature from lowering. It is because this kind of control can now be applied to machines that we have the automation we have today. Wiener was originally interested in physiology. However, he majored in philosophy and received his Ph.D. in mathematical philosophy from Harvard at the age of 18. After that, he studied under Bertrand Russell for two years, but as a Jew, landing a good teaching position in mathematical philosophy would be difficult, so at the recommendation of his father he switched to education. Until he was appointed an academic lecturing position at MIT in 1919, he changed jobs from place to place and experienced a period of misfortune. Moreover, he first realized at the age of 14 that he was a Jew, and from that point had to simultaneously make an effort to grow into a whole being. After his staff appointment at M.I.T., one of the research projects he undertook was “Mathematical analysis of Brownian Motion,” named for the English botanist Brown who, when he immersed pollen in water and observed it under a microscope, saw that the fine particles executed continuous, irregular movement. Wiener developed mathematics to deal with this type of irregular phenomena. He and some physiologists from Harvard University’s School of Medicine became devoted to this new methodology of scientific research; however, this group saw that from this point among the various fields of expertise, a new interdisciplinary field must be allowed to develop. Moreover, they noticed that the fundamental concepts connecting these were communication, control, and statistical mechanics; they created a new word, “Cybernetics,” and different disciplines such as medicine, psychology, economics, engineering, physics, pointing out the path for new progress and development, automa[tion… translator’s note: clip ends abruptly mid-word.]

As a whole, this collection offers an important new data set and, to borrow from Wiener’s lexicon, a series of “feedback loops” that enable us to retrospectively confirm or adjust our understanding of different aspects of his life and professional relationships. Some of the documents corroborate the accounts already available to us in published form. Wiener’s 1935 impressions of the differences between the Japanese universities he visited offer a case in point here. As his autobiography recalls, he noticed that “the Tokyo (University) professors looked slightly down their noses at their associates at the lesser universities”; by contrast, his impression of the Osaka University mathematics department was much more enthusiastic: “it is from this group that many of the best Japanese mathematicians have come, such as Yoshida and Kakutani, who stand among the best mathematicians anywhere” (l, p. 184). A postcard from the Ikehara collection offers a near-perfect echo of these sentiments, and adds on a note of praise for his former student. Wiener writes to Ikehara: “The Osaka school of mathematics is one of the distinguished ones in the world and I see your hand in it very clearly” (see Figure 6).

By contrast, the collection’s very existence complicates our current perception of Wiener’s global legacy. From the accounts we have of Wiener’s international influence in publications. such as Flo Conway an Jim Siegelman’s biography, his connections to Asian countries are focused first and foremost on India (with China perhaps a distant second), and Japan doesn’t garner more than a cursory mention. Dark Hero of the Information Age contains a few paragraphs about the 1935 visit (a discussion that emphasizes the increasingly xenophobic politics of pre-WWII Japanese culture and security), and its reference to the second trip is buried as a minor clause in the middle of a sentence that glosses over an entire year: “(1954) was a turnaround year for Wiener. His time in India was so successful that he was invited back the following year. On his way home. he made a lecture tour of Japan and taught a summer course on cybernetics at UCLA” (my emphasis) [4, p. 87]. The evidence from Wiener’s published accounts of his own life bolsters this sense of Japan as a very minor site of engagement: I am a Mathematician includes only a one-page write-up of the first trip, and the book was in press before he returned in the 1950s.

Thanks to the Ikehara Collection’s new archival material though, a much more robust and rich story of Wiener’s Japan connections becomes visible. We get the full schedule of Wiener’s activities. We see the multiple articles that appeared in newspapers covering the trip. We understand the range of people and audiences with whom Wiener engaged during his two months in Japan. And we know that there’s even more out there. As Hirota notes, the Ikehara Collection contains “so many documents on Wiener’s activity in Japan and (the) USA” that the material we have available so far represents only a very “carefully select(ed)” sample [5].

Perhaps most significantly, the information, images, and anecdotes we encounter in this archive allow us to grasp underexplored dimensions of Wiener’s global influence across the twentieth and into the twenty-first centuries. The archive’s timeframe is particularly noteworthy, as it reminds us that Wiener’s relationship with Ikehara spanned the decades around World War II, when tensions between Japanese and American — read, Axis and Allied — political and military institutions ran high. Given this fact, the larger Ikehara collection offers the intriguing possibility of revising our understanding of the ways in which collaborative links between the scientific communities of Japan and the United States were able to adapt or endure during the tumultuous geo-political climate of the mid-twentieth century. As more of the collection’s texts make their way into academic and public circulation, perhaps we will gain insight into how Wiener and Ikehara managed to navigate a collegial relationship within that complicated milieu. Especially given our tendencies, in the present-day, to think in stark “us-versus-them” polarities and oppositions when we address issues surrounding the use of drones and security systems, or the tensions inherent in (local) policing protocol and (international) military deployment, the continuity of Wiener and Ikehara’s friendship and professional collaborations across the mid-twentieth century might well have something to teach us.

Their relationship certainly made possible new pathways for technological innovation that continue to flourish in the twenty-first century. Hirota is explicit in offering credit to the Wiener-Ikehara connection as a driving impetus behind his country’s burgeoning information technology industry: “after Wiener’s trip in Japan, many Japanese scientists had started to study Wiener’s work under the guidance of Professor Ikehara. These events founded the current prospect of the Japanese Information Technology. So we can say that Wiener opened (the) Japanese IT world” (my emphasis) [6]. Given Japan’s high-ranking status today as a leader in IT development, Wiener’s role as an inspiration or motivator to mid-twentieth-century Japanese scientists becomes all the more significant. The notion that these documents can make us newly aware of these international, cross-temporal lines of influence nicely encapsulates the historiographic value of Ikehara’s collection: in contrast to the lack of information about Wiener’s connections to Japan that has been available to scholars of twentieth-century science and technology studies, we can now identify important lineages of mentorship running between Wiener and the Japanese scientists he reached both in person and through Ikehara’s many years of instruction.

As you read through the selection of documents from the Ikehara Collection that we have included — perhaps struggling a bit to decipher Wiener’s scrawling handwriting, or squinting at the photographs as you try to figure out what, exactly, he and his wife are eating — I hope that you get a taste of the historian’s and the biographer’s excitement. History gets written, revised, improved, and deepened through the feedback loops that archives like this one provide. And here we are, more than 50 years after Wiener’s death, only just encountering a brand new treasure trove to explore.

Figure 11. Wiener obituary. Translation: Dr. Wiener’s Thoughts Explaining the “Tragedy of the Senses.” Profound Warning to the Modern Era. Masaichi Yamazaki (trans. Nic Newby). [photo caption] The late Dr. Wiener. Eighteen days ago while traveling in Europe, Norbert Wiener passed away in Stockholm. He was born as the eldest son of Jewish scholars in Poland in 1894, and became famous as an M.I.T. professor for his statistical studies in communication theory and as the founder of “Cybernetics.” “Cybernetics” is derived from the Greek κυβερνήτης (helmsman); the English “governor” derived from the Latin form “gubernator” (ruler, governor). As an accessory governor device of the steam engine, a mechanism is devised using the centrifugal force of a pendulum to govern the steam engine’s operating speed to automatically maintain constant speed. The household electric kotatsu always comes with a “temperature control device” (thermostat) as a safety mechanism. This is an automatic regulator, designed to automatically maintain the temperature within a certain range. These automatic regulators supplied with the machine to adjust its action to a certain place can be called the machine’s pilot, the controller, the helmsman. During the Second World War, Wiener studied the automatic aiming anti-aircraft gun. The position, direction, and speed of the enemy plane is captured by radar, then that radar is automatically conveyed to a high-speed electronic computer, the computer immediately and continuously calculates the probability of the enemy plane’s expected position, the results of these computations are conveyed to a motor that moves the anti-aircraft gun, and the artillery automatically aims and fires—in this way the high-accuracy automatic anti-aircraft gun was created. The mechanism to aim at the enemy on their own, make the decision on their own, fire to kill on their own, this is is what makes these machines like living things so to speak. The radar is the sensory agency, the computer is the brain, and the gun and motor to move the gun are the reaction agency. When we move, captured information is transmitted to the brain, the brain makes a determination on these pieces of information, and it gives orders to the hands and feet. Every moment, the movements and feelings of the hands and feet are transmitted through nerves to the brain and the next action of the hands and feet are modified. By likening them to an electrical circuit such as a vacuum tube or transistor, it is possible to study the physiology of the nerves and brain. Automated machinery typical of the 17th and 18th century included the watch. The philosophers of that time often used metaphors about the watch to explain/preach their own philosophical systems. However, from the second half of the 18th century on into the 19th century, the steam engine became the representation of the automated machine. In the 20th century, the so-called “residents” of control and communication electronic machinery have become self-aware. Also for example, it is a contemporary phenomenon that not truly copying the subject but rather also considering the medium, the colors and lines themselves, making full use of the paint and brush, have become a painter’s concern. A similar twentieth century structure can be seen in both music and philosophy. It can be said that at the same time the human dominance over the environment is increasing, the danger is also increasing. Preaching Prometheus’s “tragedy of the senses”, with human respect and courage as the backbone within a cosmological pessimism , it was a matter of course that he issued a serious warning of the dangerous heaviness of fascism. In the “tragedy of the senses” he is speaking of, the world is not a comfortable nest made to protect us, it is a vast environment full of hostility and therein only through a rebellion against the gods can a bold move be achieved; moreover, the challenge herein is the sense that an according punishment is inevitable. (University of Tokyo professor, Philosophy)

Author

Full article:

JOIN SSIT

JOIN SSIT