c iStock/Jovanmandic

c iStock/Jovanmandic A Guest SSIT FutureProof Blog Post by Chey Cobb and Stephen Cobb

Enabling people to grow old in their own homes – often referred to as “aging in place” – has now been embraced by many societies as a more humane and cost-effective alternative to heavy reliance on dedicated care facilities. In terms of public policy, many governments have now embraced the idea that technology has the potential to make aging in place easier, healthier, and more affordable. As one technology journalist put it last year: “So-called ‘agetech,’ designed to address problems faced by older people, is having a moment” [1].

Whether you call it agetech or use the more traditional term, gerontechnology, the use of technology to ease the burdens of aging is part of a wider field referred Technology Enabled Care, or Technology Enhanced Care (TEC). TEC initiatives such as telemedicine have been around for a while, as has the concept of the Smart Home. What’s new in recent years is the concept of “Smart Homes for assisted living” that are enabled by a mix of technologies. These range from the Internet of Things (IoT) and the cloud, to big data analytics and Artificial Intelligence (AI).

The primary driver for agetech investment appears to be growing fears around caring for aging populations.

When you dig into the websites of companies active in agetech, the primary driver for investment appears to be growing fears around caring for aging populations: the number of older folks needing care is rising rapidly and there are fears that there won’t been enough younger workers to provide that care. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the number of people in the United States aged 65 or older will reach 95 million by 2060 and constitute nearly a quarter of the population. In the U.K., more than one in five people are already over 60.

There are fears that there won’t been enough younger workers to provide care.

The Lure of the Caring Smart Home

Here’s the pitch: millions of families are already installing smart devices, networked sensors, and voice assistants in their homes; so why not tune this increasingly affordable Smart Home to the needs of the elderly by leveraging low-cost, commercially available off-the-shelf (COTS) devices and open source software, combined with today’s ubiquitous wired and wireless broadband links, to care providers and healthcare facilities? Not only would this make life better for older folks but, think of the discoveries you could make if you turned AI loose on the massive amounts of information such a setup could generate. Over time you could gain fresh insights into elder care to iteratively improve that care, and you might just make some patentable discoveries that could be monetized to provide a return on your investment.

At first glance this pitch would seem to make perfect sense to both investors and policy makers. Indeed, governments of several countries have gone so far as to integrate athis concept into official policy. For example, in 2018, the U.K. government announced a £98 million (USD$130M) “healthy aging challenge” with the intent to “drive the development of new products and services which will help people to live in their homes for longer, tackle loneliness, and increase independence and wellbeing.”

In March of 2019, the U.S. White House published a 40-page document titled “Emerging Technologies To Support an Aging Population” (created by the Task Force on Research and Development for Technology to Support Aging Adults, out of the National Science & Technology Council). The report enthusiastically declares: “Smart homes can promote independent living and safety, and they can potentially optimize quality of life and reduce the stress and burden on aged-care facilities as well as on formal and informal caregivers.”

Stumbling Blocks

Unfortunately, both initiatives tend to skate over some of the inherent technological challenges. For example, “address the security vulnerabilities associated with IoT devices, applications, and Smart Homes” is barely more than a bullet point in the U.S. report. And the 2018 U.K. government white paper on “The future of healthcare: our vision for digital, data and technology in health and care” embraces, with no irony or hesitation, browser-based, app-driven technology, hosted in the public cloud, to leverage “the continual security and functionality improvements that come with the ‘evergreen’ ecosystem of modern browsers and web technologies.” And the paper uses the term iterate more than a dozen times, which is not reassuring to anyone who has helped frustrated users to find where the latest browser update is hiding things.

Putting a fairer value on care work is a crucial step towards a more equitable and sustainable global economy.

To be clear, the potential obstacles to using Smart Home technology as a means of helping a growing cohort of older citizens to age in place are serious and numerous. The following are just our top 10:

1) The agetech market may not be big as some optimistic projections suggest; for example, the number of older people who lack affordable access to wired or wireless broadband is not insignificant, and according to Pew Research 27% of Americans aged 65 and over don’t use the Internet.

2) The cost of adding elder-care capabilities to Smart Homes may be higher than expected, given that many older people are not tech-savvy; potentially expensive design adjustments, training, and specialized support staff may be required.

3) Gerontechnology can alleviate some human chores, but the need for care workers will not go away; and it would be unwise to expect care workers to use and support Smart Home technology without adequate training resources.

4) Low cost COTS hardware may not be reliable enough for some agetech applications, for example, if they have to meet emerging standards for care-related systems; furthermore, some IoT vendors may stop supporting products.

5) Open source software can be more costly to use than it appears; for example, either you pay for code review before you deploy, or deal with the negative impact of vulnerabilities later because you didn’t.

6) It would be unwise to assume that platform providers – such as Alphabet or Amazon – will provide their platform without some form of data gathering payoff; that may not be acceptable to some potential agetech users (according to Pew Research, negative views of tech companies have nearly doubled in the U.S. over the last four years, from 17% to 33%, and 73% of U.S. adults 50 and older think their information is less secure than it was five years ago).

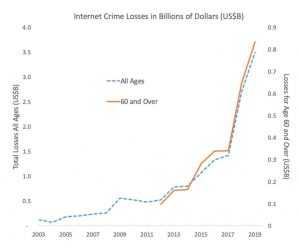

7) Preventing criminal abuse of agetech systems is a huge challenge given the abundance of attack surfaces and attackers: Internet crime losses suffered by victims 60 and over increased eightfold over the last seven years and topped $800 million in 2019 (as recorded by IC3, whose annual report, while far from perfect is nevertheless a consistent guide to crime trends).

8) A Smart Home configured for elder care may raise thorny liability issues; for example, who’s at fault if slow response to a fall leads to medical complications when company X built the system, using brand A for fall detection, B for voice commands, C for location tracking, D for voice calls, E for Internet connectivity, all joined up with brand F software, liaising with entity G for emergency response.

9 A bigger than predicted demand for elderly-assistive Smart Homes may negatively impact quality of service and customer retention if providers cannot ramp up due to a shortage of suitably skilled programmers, installers, technicians, trainers, and support staff.

10) An as yet to be determined percentage of people will oppose agetech systems if they are seen to depress wages and benefits for care workers, engage in questionable data sharing, generate excessive profits, or make unsupported claims, particularly around data protection.

Questions Answered?

With those 10 items in mind, let us address the first question: could we use Smart Home technology to solve the problems created by an aging population? We hate to say this, but the best answer is: more research required. Not that there hasn’t been a lot of research already (just google ieee aging technology – the number of hits might surprise you).

The issue is this: those 10 items have not been addressed in light of current conditions, most notably the rate at which cybercriminal activity has risen in recent years. In the U.S. last year, one form of cyberbadness – ransomware – hit 966 government agencies, educational establishments and healthcare providers. This generated all manner of service disruptions, including some that were life-threatening, not to mention unanticipated costs that undoubtedly ran into the billions. And there are many other forms of cybercrime. The FBI freely admits that the $3.5 billion in losses that were reported to IC3 are likely a small fraction of the total.

While some academic papers on assistive technology for aging in place do mention security and privacy challenges, too often it is the merest of mentions, using language like, “assuming these can be adequately addressed.” That’s a huge assumption when you look at the hockey stick curve that is unrelenting growth in cybercrime. (See Figure 1.) A much safer assumption is that the crime wave will strike Smart Home technologies, just as soon as enough people rely on them for critical functions, like caring for grandma.

Figure 1

As to the second question: should we use Smart Home technology to address issues related to aging populations? We think the answer has to be: only when levels of safety, security, reliability, and privacy protection commensurate with current conditions are achieved; and then, only if objective analysis indicates that investing in Smart Homes for the elderly is a better, more ethical use of resources than investing in growing the ranks of human care workers.

After all, if a boom in agetech exacerbates the current global shortage of suitably skilled programmers, installers, technicians, trainers, and support staff, how is that better than having a shortage of care workers? And wouldn’t it be better to reduce that shortage first? Of course, market-oriented economists like to say “shortage of workers at current levels of remuneration,” and they have a point. Indeed, putting a fairer value on care work is seen by many social reformers as a crucial step towards a more equitable and sustainable global economy [2]. We think the benefits to society of putting resources into the development of agetech – which is clearly not a risk-free proposition – must be assessed relative to alternatives use of those resources, such as providing decent wages, training, and benefits to a human care workers.

References

[1] J. Margolis, “Agetech could transform the care industry: Apps to keep relatives safe are effective but may not appeal to older technophobes,” FT Financial Times, July 19, 2020; https://www.ft.com/content/ba4d0376-a7be-11e9-90e9-fc4b9d9528b4.

[2] M. Lawson et al., “Time to care: Unpaid and underpaid care work and the global inequality crisis,” Oxfam International, 2020; https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/620928/bp-time-to-care-inequality-200120-en.pdf.

Authors

Stephen Cobb is an independent public-interest technology researcher with a 30-year background in cybersecurity and data privacy. He is @zcobb on Twitter and can be reached via the scobb.net website.

JOIN SSIT

JOIN SSIT