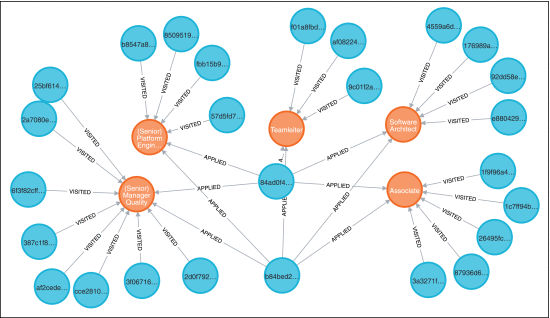

Figure 1.Typical graph of interactions between the potential candidates and job advertisements: orange circles are job postings; blue circles are website visitors; and the connections shown as lines are “visited” and “applied.” Not shown are other possible interactions, such as “download,” “share,” and “play video.”

Figure 1.Typical graph of interactions between the potential candidates and job advertisements: orange circles are job postings; blue circles are website visitors; and the connections shown as lines are “visited” and “applied.” Not shown are other possible interactions, such as “download,” “share,” and “play video.” Olena Linnyk and Ingolf Teetz

There are three common beliefs about the labor market: first, that increased use of artificial intelligence (AI) is going to cause large-scale unemployment in the future; second, that the post-pandemic revitalization of mobility and migration would resupply the markets affected currently by the workforce shortage; and third, that job postings, under existing employment laws, do not use biased language and offer equal opportunities to job seekers. All of them are wrong.

In the future, we will face labor shortages globally. According to recent studies, the imbalance between available jobs and the skilled workforce is not due to robots taking away jobs, but on the contrary, to a shortage of qualified human candidates to fill the vacancies [1].

The imbalance between available jobs and the skilled workforce is not due to robots taking away jobs, but to a shortage of qualified human candidates to fill the vacancies.

Migration, instead of solving the problem, can rather lead to a deeper disparity between the “West” and the global South. In fact, a serious concern is that a new form of colonialism appears to be emerging. Historically, developed nations have exploited the resources and cultures of less developed countries. However, the current situation suggests that wealthy countries are now about to be draining the disadvantaged nations of their skilled labor force, leaving them without vital professionals.

Biased language in job postings is still widespread and hinders large population groups from participating in the workforce. On the other hand, thoughtful application of AI technology may be the key to reducing the bias and ineffectiveness in job advertisements and in recruiting generally.

It is fascinating to relate the fundamental theories behind human behavior with the patterns, hidden within the labor market data. The data reveals an imminent crisis that threatens not only individual companies and nations, but the entire global community as well. By 2030, most countries will face labor shortages and there will be significant labor imbalances worldwide. For instance, the World Health Organization reported [2] the expected shortage of over 10 million health workers in 2030. It is projected that the world’s combined gross product will fall by $10 trillion because the nations will not be able to fill vacant jobs [3].

For example, in Germany, the crisis is already in full swing, with labor force shortages manifesting as a national security issue. Today, the talent deficit already at hand is 2.4 million workers, projected to be up to 10 million by 2030 when the labor supply in Germany is expected to shrink from around 43 million people today to 37 million. Germany sees already a shortage not only of engineers and information-technology (IT) specialists, but also of care workers, teachers, and other professionals [3], [4].

Thoughtful application of AI technology may be the key to reducing the bias and ineffectiveness in job advertisements and in recruiting generally.

Elsewhere in the world, the problem is also beginning to emerge, for instance, the United States alone needs to hire additional half a million cooks in restaurants in the next decade. The shortage of nurses is a pervasive problem across countries, and the situation worsens when we consider the prospect of needing to hire hundreds or thousands more of them in the next 10 years [8]. Initially, it was believed that the pandemic caused a shortage of workers due to the lack of mobility and immigration. However, the situation has only worsened post-pandemic [7].

The true challenge is that the workers’ mobility that helps mitigate the issue in some countries will simultaneously jeopardize the perspectives of the labor market in others. Developing countries are already losing some of their valuable workers to richer countries. For example, most of the medical doctors trained in Mozambique emigrate and work abroad [5]. Unfortunately, we are not currently heading in the right direction to solve this issue, and it is a situation that eerily echoes the environmental crisis of the past.

Clearly, there is no one immediate mitigating solution to address the multiple societal factors that contribute to the crisis. While political solutions are still in progress, technological solutions, such as telemedicine, can boost productivity and enable remote collaboration, thereby preventing the situation from escalating into a global security issue. Furthermore, technology can optimize the recruiting process and improve the participation of underrepresented groups in the labor force.

Germany sees already a shortage not only of engineers and information-technology specialists, but also of care workers, teachers, and other professionals.

For instance, AI can optimize recruiting, ensuring that individuals find jobs that fit them well. AI applications in question include programmatic advertising for the optimized impact of job ads and timely bringing together job offers and suitable applicants; effective communication with applicants through AI-based chatbot systems; and augmented writing for bias-free and gender-neutral wording for job advertisements. Indeed, it is becoming increasingly important that job postings are formulated and distributed in such a way that they have the greatest possible impact, and no group of suitable applicants feels excluded.

Observing the interaction of job seekers with web-based job advertisements proved to be an invaluable tool to better understand their habits and tendencies. We show in Figure 1 a snapshot of the graph for the relevant interactions of visitors to the job portal Jobstairs [15] with the job advertisements. The combination of our analysis and the statistics data in Germany [4] reveals that it can take over half a year for a company to fill an IT job vacancy, while job seekers with IT-related qualifications may still spend months searching for a job that matches their skills. This situation is unfortunate for both the companies and the candidates.

By using natural language processing to analyze text-based communication, we can optimize the matching process. Transforming words and sentences into mathematical objects enables computers to understand language and match candidates with job requirements based on qualifications [9] without considering other, personal information. The purpose of the prematching procedure based solely on skills is to reduce possible biases in the recruitment process. However, for the algorithm to be accurate, it is crucial that the computer understands whole sentences, not just single words. This can be achieved, for instance, by applying the transformer-based language models trained on domain-specific data. Optimizing the recruitment process in this way not only prevents some unintended bias, but also significantly reduces the duration of the process, saving time and money for both job seekers and employers.

Our language models are designed to understand the nuances of words within the context of a job advertisement. To illustrate this, let us demonstrate an example from our matching algorithms [9], designed for application in the German language space. The job advertisement states: “Wir suchen einen Bäcker mit Informatikstudium und Erfahrung als Bäcker. Wir bieten Leistungen wie frisches Brot vom Bäcker. Ihr Ansprechpartner ist John Bäcker.” The word “Bäcker” is used in various contexts within this text, and our program can differentiate between them. It can determine whether “Bäcker” is used as a skill, a benefit, or as a name. This differentiation is crucial for accurately matching candidates with job requirements. Additionally, we are using a data-driven ontology in contrast to the expert-knowledge systems like, for instance, the ESCO—the European Skills, Competences, and Occupations taxonomy [10], so that our program automatically learns and updates the skill list based on new data. For instance, if, in the future, backers would need to have knowledge of quantum computing, our program will incorporate this into its list of required skills (see Figure 2 for illustration).

Figure 2.Example output of the natural language understanding (NLU) module for the extraction of skill from the job posting text for the matching algorithm [9].

In our efforts to further optimize the recruiting process, we have also developed an application that specifically aims to reduce gender bias in German-language job advertisements [11]. Even before a recruiter sees a candidate, their unintended bias toward a stereotypical professional can be incorporated into the wording of the job advertisement through the choice of gender-stereotypic adjectives and nouns describing the person they are looking for and the vacancy itself [17], [18], [19], [20], [21]. The famous scandal related to the discrimination of female candidates for IT-related jobs at Amazon had a similar cause [28].

Additionally, the exact wording of the posting is important because it defines to which potential candidates it will be shown by automatic recommendation systems. In particular, the targeted playout of job advertisements to specific audiences through intelligent marketing systems harbors a significant risk of promoting discrimination and prejudice [6]. For example, a study found that a Facebook recommendation system, unfortunately, has shown job postings for taxi drivers in the United States predominantly to people of color because of the stereotypical description of these jobs [12], [13].

To mitigate bias in the wording of job postings, we employ psychological theories to analyze language usage and determine the sentiment of a text [16]. If bias is detected, our program suggests alternative gender-neutral synonyms and neutral sentence structures to recruiters [17]. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the final decision ultimately lies with the human recruiter. By leveraging technology to reduce bias in formulations of job advertisements, we give companies the possibility to create a more equitable recruitment process for all candidates as well as reach a larger candidate pool.

By analyzing usage data from the job portal Jobstairs [15], we have found that one can significantly increase the number of job applications per visitor of advertisements by changing the text of the vacancy description to have fewer stereotypical male formulations (see Figure 3). The results confirm the findings of previous studies [17], [18], [19], [20] that female test persons are more willing to apply for jobs when the language used in the advertisement was less biased toward the stereotypically manly-connoted sentiment. It was previously assumed that men were not affected by biased language. Our data, however, have shown that both women and (to a lesser degree) men are more likely to apply if the advertisement is formulated with fewer male-connoted words [14], [16]. This has important implications for recruiters who want to increase their applicant pool while enhancing its diversity [21].

Figure 3.Results of an A/B-test comparing the number of applications per 100 visitors (readers) of the job advertisement web pages before and after the reformulation of the text by removing the strongly man-connoted words (based on analysis of 50 advertisements and about 1,000 visitors).

In addition to the possibilities opened by AI applications in recruiting, we must emphasize the potential new risks. The expectations of rationality and neutrality are not necessarily fulfilled by AI decision systems trained on historical data of human decisions. Based on statistical learning, even the best AI models available are not immune to learning bias from us humans. For example, a state-of-the-art image-generating model [22] exhibits gender bias. If asked to produce an image of a “flight attendant,” it would create only pictures of women [23], even though the term “flight attendant” is gender-neutral [24]. Similarly, when asked to produce an image of a “lawyer,” it would only generate images of men. A similar bias is also present in the outputs of the currently best text-generating model [25].

The expectations of rationality and neutrality are not necessarily fulfilled by AI decision systems trained on historical data of human decisions.

The reason for this bias is the data used to train the models. When one searches for images of a “teacher” (or German: “Lehrkraft”) on Google, most of the results are pictures of women, even though this is a gender-neutral job title [26]. The bias is not due to technology, but rather to our human biases in the training data. The problem is, however, that AI models amplify human bias due to the limitations of the representation space, which focuses on the statistically most important parameters and excludes others [27]. As a result, serious consequences can arise, such as AI systems that discriminate against people of color or refuse to offer high-paying jobs to women [28]. Thus, transparency and fairness of all algorithms used in the recruitment process must be ensured.

Amid a global labor force crisis, we cannot turn a blind eye to technological solutions. However, we must approach them with caution and prudence to avoid exacerbating existing biases. While we may not have all the answers on how to completely solve this problem yet, it is our responsibility to ensure that a new form of colonialism does not evolve as a means to counteract the growing labor shortages. It is important to remember that even in times of crisis, we cannot compromise our values and allow bias and discrimination to go unchecked.

Author Information

Olena Linnyk is the head of the Artificial Intelligence Lab at Milch&Zucker AG, 35398 Giessen, Germany, and a lecturer in deep learning at the Departments of Natural Sciences and Medicine, University of Giessen, 35392 Giessen, Germany. She researches at the Frankfurt Institute for Advance Studies, Frankfurt, Germany, on information extraction from incomplete and noisy data and bias reduction in AI systems. Email: Olena.Linnyk@milchundzucker.de.

Ingolf Teetz is the CEO of Milch&Zucker AG, 35398 Giessen, Germany, one of the most innovative companies in Germany providing software products for talent and job advertisement management, excellent candidate experience, and HR process automation. He is an active member of the HR Open Standards Consortium, which promotes openness and fairness in HR technology.

To view the full version of this article, including references, click HERE.

![Figure 2. - Example output of the natural language understanding (NLU) module for the extraction of skill from the job posting text for the matching algorithm [9].](https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/mediastore_new/IEEE/content/media/44/10174794/10174814/linny2-3277108-small.gif)

JOIN SSIT

JOIN SSIT