Norbert Wiener and the Call for Ethical Engagement

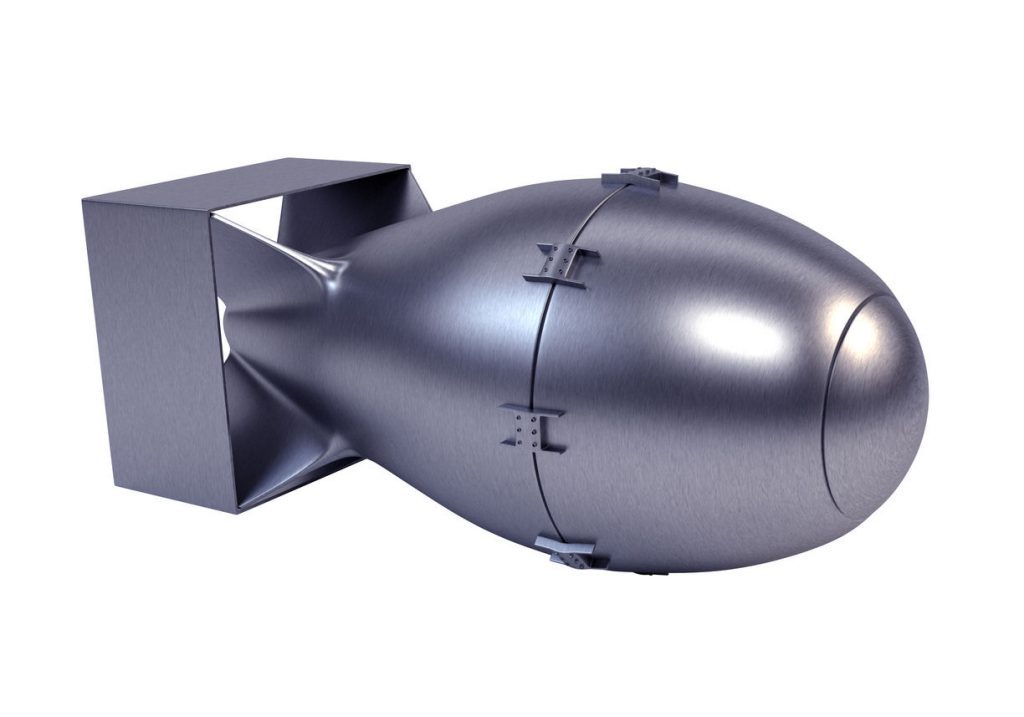

Over the last century, the greatest acceleration of technological development has come during times of conflict and war. The impetus for these flurries of innovation has been the need for nation states to keep one step ahead of their enemies by conceiving, creating, and closely guarding the technological secrets behind ever-more complex weaponry with ever-greater destructive capacity. The offensive tactic that emerges is characteristic of modern asymmetric warfare, where competing forces perpetually threaten one another: “Comply at once!” they seem to say, “or we will unleash our arsenal on you, the terrible consequences of which will leave you no choice but to comply!”

Underlying this military logic is a particular form of synergy forged by collaborations between classified operations research and the industrial and systems engineering fields. It rose to prominence during World War II and set the stage for the large-scale information-processing and complex machine-building projects that have proliferated over the last seventy years. For reasons rooted in military tactics and strategy, many of these technological projects take place behind closed doors and are not available for public scrutiny. Nonetheless, they have led to breakthroughs that also circulate in the open market. These products (or parts thereof) were initially developed for use within the military sector but become available – albeit in slightly modified forms – to a global public that is eager to access and use new tools and gadgetry. Among the list of technologies that have emerged through these types of “military-to-market” adaptations are: mechanical calculators, radio-frequency identification (RFID) sensors, satellites, the Internet, Global Positioning Systems (GPS), and drones. Many of these technologies provide practical services that make previously complicated tasks more convenient and accessible; however, thanks to the ease and speed with which new technological devices become integrated into our daily lives, it is easy to ignore the more ethically problematic dimensions of the larger (often nebulous) systems that make those tools available to us.

Military projects have led to breakthroughs that also circulate in the open market.

Take, for instance, the way that the close relationship between military and consumer production processes can lead to the perception of war as a beneficial (or at least necessary) catalyst for kick-starting and sustaining technological production, employment, and economic growth – and therefore, as something not to be questioned. In his 2006 book, Is War Necessary for Economic Growth?: Military Procurement and Technology Development, Vernon W. Ruttan admits as much, noting that he “find(s) it very doubtful, in the absence of at least the threat of major war, that the U.S. political system could be induced to mobilize the very large scientific, technical, and fiscal resources” upon which both military and general-purpose technological developments depend. Indeed, he posits that “it was access to large and flexible resources that enabled powerful bureaucratic entrepreneurs … to mobilize the resources necessary to move the general-purpose technologies from initial innovation toward military and commercial viability” [1, p. 184]. While we may appreciate the end result of these processes as we surf the web for travel deals or Skype with family and friends around the world, Ruttan’s remarks also suggest that it is important to recognize how those services might also be bound up in larger institutional structures with far less socially benign ambitions. An earlier, and more public, proclamation of the problematic implications of these types of relationships appeared in U.S. President Eisenhower’s 1961 Farewell Address, where he made reference to the informal alliance between the military and defense industries. As he warned, “we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex” [2]. The call Eisenhower makes to his listeners – to resist the expansion of the military’s “unwarranted influence” in society – helpfully sets up the key concepts that this article will explore, namely the ethical quandaries raised by twentieth-century military, industrial, and commercial technologies, and the approaches we might take to engage responsibly with these issues.

Wiener’s Warnings

Eisenhower, a former World War II Army General, was certainly not the first public figure whose experiences during the war prompted reflection on the ethical problems inherent in the military’s increasing (yet not always recognized) sphere of influence, and the responsibilities of citizens to respond to and resist that trend. Several years earlier, Norbert Wiener – the M.I.T. mathematician to whom this special issue is dedicated – had staked out similar ground in the context of scientific contributions to military projects. As part of his wartime research, Wiener had developed a prototype for an automatic anti-aircraft gun. However, in a January 1947 letter to the Atlantic Monthly, which was published as “A Scientist Rebels,” he proclaimed:

“The policy of the government itself during and after the war, say in the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, has made clear that to provide scientific information is not a necessarily innocent act, and may entail the gravest consequences. One therefore cannot escape reconsidering the established custom of the scientist to give information to every person who may inquire of him. The experiece of the scientists who have worked on the atomic bomb has indicated that in any investigation of this kind the scientist ends with the responsibility for having put unlimited powers in the hands of the people whom he is least inclined to trust with their use. It is perfectly clear also that to disseminate information about a weapon in the present state of our civilization is to make it practically certain that the weapon will be used. … If therefore I do not desire to participate in the bombing or poisoning of defenseless peoples—and I most certainly do not—I must take a serious responsibility as to those to whom I disclose my scientific ideas” [3, p. 46].

“The bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, has made clear that to provide scientific information is not a necessarily innocent act, and may entail the gravest consequences,” Wiener said.

Wiener devotes a full chapter of his 1956 autobiography to a discussion of these ideas, explaining in detail the development of his perspective on the Manhattan Project and his approach to ethics in postwar life and society. He states that “the most important thing about the atomic bomb was, in my opinion, not the termination of a specific war without undue casualties on our part, but the fact that we were now confronted with a new world and new possibilities with which we should have to live ever after” [4, p. 299]. As his argument unfolds, we understand that the consequences of this “new world” and its “new possibilities” extend, for Wiener, beyond the arena of combat into the realm of everyday life for ordinary citizens. He recalls that during the war, he “had already begun to reflect on the relation between the high-speed computing machine and the automatic factory,” and had surmised that “the automatic factory was not far off.” In light of this state of affairs, Wiener muses, “I wondered whether I had not got into a moral situation in which my first duty might be to speak to others concerning material which could be socially harmful” [4, p. 295]. A few pages later, he proclaims: “I thus decided that I would have to turn from a position of the greatest secrecy to a position of the greatest publicity, and bring to the attention of all the possibilities and dangers of the new developments” [4, p. 308]. In these passages, we can see that Wiener – as a well-informed scientist – considered it not merely optional, but rather ethically imperative to speak out about how new technological developments that were quietly advancing in industrial and military fields might have disastrous consequences for society at large.

Large-Scale Industrial Unemployment in the Face of Automation

Wiener’s dedication to following through on this choice to call public attention to the potential dangers of technological development is evident not only in documents like “A Scientist Rebels” (as we’ve noted above), with its overt critique of the military, but also in his 1949 letter to Walter Reuther, the head of the American Auto Workers Union. In that correspondence, Wiener warned of the potential for “large scale industrial unemployment” in the face of automation [5]. Throughout the later years of his life, Wiener had much to say about the ethical obligations members of the scientific community faced in their approach to collaboration with both the military industrial complex and the broader world of technological innovation [6, p. 38]. He drew stark lines separating what he considered the appropriate (i.e., socially beneficial) uses of science from those he deemed unethical. and he was willing to put his professional reputation on the line to uphold those divisions.

Wiener refused to work on projects with potential applications to weaponry, war, and the ultimate killing of human beings.

In many ways, Wiener’s career was short-circuited by this stance. He refused to work on projects with potential applications to weaponry, war, and the ultimate killing of human beings. In particular, he eschewed any government grants funded by the U.S. Department of Defense. Consequently, as Cornell Professor in History and Ethics of Engineering Ronald Kline has argued, Wiener did not garner the acclaim that he might have secured with continued contributions to military projects [7]. Despite the fact that he had spearheaded cybernetics research – he is known, after all, as the “father of cybernetics” [8] – Wiener had to sit on the sidelines as his discipline found “an American home in two military-funded, interdisciplinary research laboratories in the 1950s” – M.I.T.’s Research Laboratory of Electronics, and the University of Illinois’ Biological Computer Laboratory [7, p. 101]. Furthermore, his own institution of M.I.T. hired Jerome Wiesner (not Wiener) to head their new cybernetics research unit [7, p. 65].

Environmental Crisis in the Wake of Resource Exploitation

These disciplinary developments and professional snubs, however, did not stop Wiener from travelling widely to many parts of the world, working on important research in various crossdisciplinary fields, and championing issues related to ethics and sustainability [9]. He was cognizant that prof- it maximization underlined some of the greatest decisions by government and business, and that their approach to commerce posed grave threats to the environment. “In a profit-bound world,” he wrote in 1956, “we must exploit [the natural world] as a mine and leave a wasteland behind us for the future” [10, p. 362].

Two years earlier, Wiener had already drawn attention to the urgency of global resource management. Citing impending shortages in “essential resources” ranging from metals (iron, copper, lead, and tin) to fresh water (in particular in places like California) and food, Wiener proclaims to readers that

“the ever-increasing growth of technique, and the particularly accelerated growth due to a couple of great wars and a prolonged period of military tension, have made many of these shortages matters of reasonably present [rather than long-term, future] concern, to which we must devote at least a considerable part of our planning potential at this day and moment” [11, p. 2f].

Wiener drew attention to the urgency of global resource management.

Collectively, these remarks recall his 1950 warning (which is all the more prescient in light of current international debates about how to best tackle the problem of climate change): our “Mad Tea Party” approach to resource extraction, Wiener posits, will make us

“the slaves of our own technical improvement … [because] we have modified our environment so radically that we must now modify ourselves in order to exist in the new environment” [12, p. 45f].

Wiener’s Legacy: Protesting the Military Use of Cybernetics

As we have noted (and others have argued in more detail [13], Wiener was a very harsh critic of the cooption of cybernetics for military use, and staunchly refused to contribute to any scientific research projects that he believed might inadvertently make possible enhanced forms of destructive technology. In his 1956 autobiography, he was explicit about what he saw as the most frightening sociological implications of the atomic bomb: “for the first time in history, it has become possible for a limited group of a few thousand people to threaten the absolute destruction of millions, and this without any highly specific immediate risk to themselves” [4, p. 300]. The focus of Wiener’s critique here is not merely the increased destructive capability of new weapons technology; it also, and perhaps more importantly, highlights the ways these updated technologies distance and shield the perpetrators of twentieth-century mass violence (along with their countries’ citizens) from the horrors experienced by victims. In light of this structurally enabled separation from the violent consequences of our own actions, Wiener’s impulse to speak out and expose the dangers of twentieth-century warfare and social injustice gains heightened significance. It offers a model for activism and ethical engagement.

During the years leading up to and following Wiener’s death in 1964, other scientists and scholars also called attention to these ethically problematic gaps. To cite just one prominent individual, the American philosopher, historian of technology, and famously eclectic thinker, Lewis Mumford adopted a similarly polemical stance when he became one of the first American scholars to openly speak out against the Vietnam War. His 1965 letter to President Johnson appeared on March 3rd in the San Francisco Chronicle, and was reprinted two days later in The Dispatcher[14]: “The time has come,” he writes, “for someone to speak out on behalf of the great body of your countrymen who regard with abhorrence the course to which you are committing the United States in Vietnam… I have a duty to say plainly, and in public… that the course you are now following affronts both our practical judgment and our moral sense… [and] cannot have any final destination short of an irremediable nuclear catastrophe” [15, p. 3].

Many others joined ranks with Mumford to speak out against the use of science for destructive aims during the Vietnam War era, some even forming coalitions to increase the reach of their collective voice. As early as 1957, the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs responded to the threat of nuclear war, as the United States and the Soviet Union armed themselves with nuclear weapons. Organizations like the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), and Science for the People, were established to stimulate an awareness of the political, social, and economic factors affecting science and technology [16]. The UCS boasts a particularly salient connection to Wiener, given that it was founded in 1969 by M.I.T. physicists Kurt Gottfried and Henry W. Kendall. The organization aimed to “tap the power of science, to stem the threat posed by science itself” by “calling for scientific research to be directed away from military technologies and toward solving pressing environmental and social problems” [17]. To this day, the UCS continues to champion “innovative, practical solutions to some of our planet’s most pressing problems” as it strives to “build a healthy planet and a safer world” [18] – these are precisely the goals that Wiener had so loudly championed earlier in the century.

In short, a range of thinkers and practitioners have continued Wiener’s legacy of demanding ethical vigilance around the development and implementation of new technology. After all, as this chorus of voices warns us, even technologies that scientists, engineers, and mathematicians develop for what they consider ethically sound purposes can end up in the wrong hands, and therefore lead to loss of life. In retrospect, we can see how Wiener’s warnings established a framework for future engagements with technological ethics. He helped us see how important it is to understand the intricate ways in which technology is enmeshed in a network of sociological. ethical, political, and interpersonal factors.

Interdisciplinary Resonances: Science, Technology and Society

As we have outlined, in the decades following World War II, concerns about the dangers of military and industrial technologies led to a wider movement among intellectuals and technicians to organize around goals that aligned closely with Wiener’s perspective. Parallel to this widespread social activism, the label “Science, Technology, and Society” emerged in the academy in the 1970s as a means to identify a diverse group of intellectuals who were united by progressive goals and an interest in science and technology as problematic social institutions. For such researchers (and, again, in keeping with Wiener’s ideas), the project of understanding the social nature of science has generally been seen as continuous with the project of promoting a socially responsible science. What developed into the field of Science and Technology Studies (STS) started from the assumption that all technologies are inherently social insofar as they are designed, produced, used and governed by people [19], [20].

It is worth stressing that, from the outset, the objection to technological determinism was and is political as well as intellectual. Many of the people who got involved in the development of this field in the 1980s had a simple polemical purpose, to shake the stranglehold that a naïve determinism had on the dominant understanding of the intertwining of society and technology. They were concerned that this view of technology, as an external force exerting an influence on society, narrows the possibilities for democratic engagement. It presents a limited set of options: uncritical embracing of technological change, defensive adaptation to it, or simple rejection of it. Against this perspective, STS is founded on a belief that the content and direction of technological innovation are amenable to sociological analysis and explanation, and to political intervention.

The field of STS provides a window into the interdisciplinary resonances of Wiener’s approach to understanding technology’s social implications, particularly its imbrication in the power dynamics of various social hierarchies. Most often, when we speak of a “society,” we are referring to the collective citizenry who belong to a given region. At times they are powerless, at other times they are able to demand certain forms of change. Dependent on the economic and political systems in place, the latitude for enacting change differs.

However, when it comes to the type of high-stakes military affairs that we mentioned at the beginning of this article – i.e., when things like potential enemy advancement or military contracts are up for discussion—the dominant change-makers have always been governments, big business, and the scientific elite. Against the interests of these powerful groups, the voices of ordinary citizens, who have every right to protest and ask “where are we headed” and “why are we going this way,” often get drowned out or overlooked.

Furthermore, the speed with which information travels since the creation of the Internet means that decision-making often happens faster than the public can even come to terms with the ideas and projects under consideration. Before we know it, troops have been deployed, drones are dropping payloads, and innocent people (including children) have lost their lives.

Our Shared Ethical Responsibility for Technological Development

Wiener’s approach to ethics teaches us that all humans have a responsibility to shape technology in a way that minimizes harm and maximizes benefit, and to critically reflect on our individual contributions to (and, by extension, complicity within) those processes. After all, while his work laid the basis for factory automation and many of the destructive technologies we see in the 21st century, Wiener was also one of the first public figures to call attention to both negative and positive impacts of these trends, and to modify his approach to research in ways he deemed morally appropriate. In short, he saw himself not simply as a professor of mathematics, but more importantly a member of society at large – a person with ethical obligations to his fellow citizens and the world.

All humans have a responsibility to shape technology in a way that minimizes harm and maximizes benefit.

In addition to the diverse ways that approaches similar to Wiener’s have been taken up by scientists, academics, and activists across a range of disciplines, his example offers a model for global citizens of the twenty-first century as we navigate our own ethical relationships to the ever-changing world of technological tools. His work prompts us to recognize that, as mindful educators, inventors, developers, and entrepreneurs, we should not be building simply for novelty’s sake. Instead, we need to be asking ourselves (and our students) tough ethical questions:

- Who is shaping the direction and purposes of technological innovation. today?

- What motivates their engagement within these processes and fields?

- In what ways are they shaping society?

- How do other stakeholders become more influential in making decisions about the technology process?

- How are government and industry communicating with the public about the developments taking place?

These questions urge us not to succumb to the type of willful blindness Wiener criticized in what he saw as the mid-twentieth-century public’s failure to resist the shroud of secrecy cloaking military uses of science: “It is the great public which is demanding the utmost of secrecy for modern science in all things which may touch its military uses. This demand for secrecy is scarcely more than the wish of a sick civilization not to learn of the progress of its own disease” [12, p. 127]. By following Wiener’s lead, we are instead prompted to actively engage with – and speak out about – the ethical conundrums that accompany technological progress as it unfolds in the present day.

As we write, the future of artificial intelligence, robotics, big data, and employment are being hotly contested within many communities (e.g., political, economic, sociological. technical, cultural). Some of the biggest players in the digital revolution (Facebook, Google, Microsoft, IBM and Amazon) have partnered to address AI’s ethical problems, even if it has been “after the fact.” Yet the members of this “internal” ethics board, let alone the activities of these companies, are shrouded in mystery. The assumption upon which they operate seems to be, “we (thanks to our technical expertise and economic success) know what is best and can be trusted to regulate ourselves.” We hope it is clear that this perspective would not have satisfied Wiener. Unless there is much more transparency about what these and other corporations are developing, and wider involvement of and communication with external experts and the public, it will be impossible to ensure that the technologies that emerge are in the best interests of society. Groups like the IEEE’s Global Initiative for Ethical Considerations in Artificial Intelligence and Autonomous Systems offer a step in the right direction, but as Wiener reminds us, we all – engineers, academics, scientists, and especially everyday citizens – have an ethical obligation. We must find ways to listen closely and to make our voices and our values heard in these important debates as technology’s role in shaping the world around us continues to evolve [21].

JOIN SSIT

JOIN SSIT