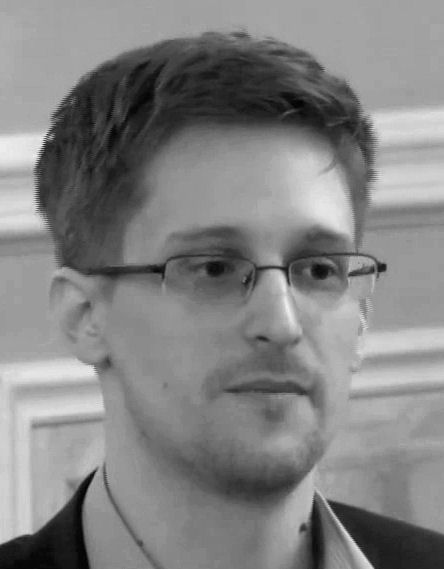

In June 2013, Edward Snowden burst onto the world media scene. He had worked as a contractor for the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) and collected a vast quantity of top-secret documents. Snowden leaked the documents to the Guardian, a well-known British newspaper and media group, revealing that the NSA had been secretly carrying out extensive spying on electronic communications.

Snowden quickly became one of the world’s best known whistleblowers. As well as extensive commentary in the mass and social media, several major books have been published about him and his revelations [1]–[2], [3].

Lessons for Whistleblowers

I have been studying suppression of dissent since the late 1970s and have talked with hundreds of whistleblowers, seeking to provide practical advice [4]. So naturally I was impressed by Snowden’s efforts and especially by his success in raising public awareness about surveillance.

Whistleblowers are people, typically employees, who speak out in the public interest, and most of the time they reveal their identity immediately, such as when they report a problem to the boss or some internal body. Unfortunately, this is disastrous much of the time: the whistleblowers are attacked—for example ostracized, denigrated, reprimanded, sometimes dismissed—and furthermore their access to information is blocked. As soon as their identity becomes known, they have limited opportunities to collect more information about wrongdoing.

For these reasons, it is often advantageous for whistleblowers to remain anonymous, and to leak information to outside groups, especially to journalists or action groups. The leaking option reduces the risk of reprisals and enables the leaker to remain in the job, gathering information and potentially leaking again. Furthermore, stories based on leaks are more likely to focus on the information, not the leaker.

Although few whistleblowers reveal information warranting international headlines, every effort at speaking out in the public interest is important and hence worth doing as well as possible. Snowden’s experiences provide several valuable lessons for other whistleblowers.

Lesson 1: Be Incredibly Careful

Snowden leaked the most top-secret information of anyone in history, but it wasn’t easy. The lesson from his experiences is that to be a successful leaker, you must be both knowledgeable and extremely careful. Snowden had developed exceptional computer skills. He was leaking information about state surveillance, and he knew the potential for monitoring conversations and communication. He took extraordinary care in gathering NSA documents and in releasing them. When he contacted journalists, he used secure email. When meeting them, he went to extreme lengths to screen their equipment for surveillance devices. For example, before speaking to journalists, he had them put their phones in a freezer, because the phones might contain monitoring devices.

Few whistleblowers need to take precautions to the level that Snowden did: his enemies were far more determined and technically sophisticated than a typical whistleblower’s employer. Nevertheless, it is worth learning from Snowden’s caution: be incredibly careful.

Lesson 2: Choose Recipients Carefully

Snowden carefully considered potential recipients for his leaks. He wanted journalists and editors who would treat his disclosures seriously and have the determination to publish them in the face of opposition by the U.S. government. He decided not to approach U.S. media, which usually are too acquiescent to the government. U.S. media have broken some big stories, but sometimes only after fear of losing a scoop. The story of the My Lai massacre, when U.S. troops killed hundreds of Vietnamese civilians during the Indochina war, was offered to major newspapers and television networks, but they were not interested. In 2004, U.S. television channel CBS initially held back the story about abuse and torture of Iraqi prisoners by U.S. prison guards at Abu Ghraib prison, at the request of the Pentagon, finally going to air because the story was about to be broken in print.

Snowden decided instead to approach the Guardian, a British media group with a history of publishing stories in the public interest, despite government displeasure. It was a wise choice.

Lesson 3: Be Persistent

Snowden decided to approach the Guardian, and not just anyone: in late 2012 he contacted the Guardian‘s freelance columnist Glenn Greenwald, noted for his outspoken stands critical of U.S. government abuses, especially surveillance. Snowden sent Greenwald an anonymous email, offering disclosures and asking Greenwald to install encryption software. However, Greenwald—resident in Brazil—was busy with other projects and didn’t get around to it. So Snowden created a video primer for installing the software just to encourage Greenwald to use it. However, even this wasn’t enough to prod the busy Greenwald to act.

Snowden didn’t give up. In January 2013, he next contacted Greenwald’s friend and collaborator Laura Poitras—a fierce critic of the U.S. security state, and a victim of it—who he thought would be interested herself and who would get Greenwald involved. It worked.

The lesson is to be persistent in seeking the right outlet for leaks—and to be careful and patient along the way.

Lesson 4: Improve Communication Skills

Snowden is a quiet, unassuming sort of person. He might be called a nerd. Contrary to some of his detractors, it was not his desire to become a public figure. Despite his retiring nature, Snowden knew what he wanted to say. He refined his key ideas so he could be quite clear when speaking and writing, and he stuck to his message.

Most whistleblowers need good communication skills to be able to get their message across. (In a few cases, leaking documents without commentary might be sufficient.) My usual advice is to write a short summary of the issues, but this isn’t easy, especially when you are very close to the events. Being able to speak well can be just as important, if you have telephone or face-to-face contact with journalists or allies. Many people will judge your credibility by how convincing you sound in speech and writing. Practice is vital, as is feedback on how to improve.

Lesson 5: Make Contingency Plans

Snowden thought carefully what he wanted to achieve and how he was going to go about it. Initially he leaked selected NSA files to journalists to pique their interest and demonstrate his bona fides. After all, who’s going to believe someone sending an email saying they can show the NSA is carrying out massive covert surveillance of citizens and political leaders? After establishing credibility, Snowden then arranged a face-to-face meeting, to hand over the NSA files and help explain them: many of the files were highly technical and not easy for non-specialists to understand.

Snowden knew that it would be impossible for him to remain in hiding. The U.S. government would do everything possible, technically and politically, to find and arrest him. So Snowden decided to go public, namely to reveal his identity (though Greenwald convinced him to wait a few days after the initial media stories). Going public added credibility to the revelations by attaching them to a human face.

He did not anticipate every subsequent development: it was not part of a plan to flee Hong Kong and end up in Russia. Even so, Snowden anticipated more of what happened than do most whistleblowers, who are often caught unawares by reprisals and stunned by the failure of bosses to address their concerns and of watchdog agencies to protect them.

The lesson from Snowden is to think through likely options, including worst case scenarios, and make plans accordingly.

Lesson 6: Be Prepared for the Consequences

Snowden knew that leaking NSA documents would make him a wanted man. He was prepared for the worst scenario: arrest and lengthy imprisonment. He knew what he was sacrificing. Indeed, he had left his long-time girlfriend in Hawaii, knowing he might never see her again. He made his decision and followed it through.

So far, Snowden has avoided the worst outcomes, from his point of view. He might have ended up in prison, without access to computers (his greatest fear), perhaps even tortured like military whistleblower Chelsea Manning. Still, living in Russia—an authoritarian state, where free speech is precarious—is hardly paradise. Snowden is paying a huge price for his courageous actions. He knew he would, and he remains committed to his beliefs.

Whistleblowers seldom appreciate the venom with which their disclosures will be received. It is hard to grasp that your career might be destroyed, and perhaps also your finances, health and relationships. It is best to be prepared for the worst, just in case. Being prepared often makes the difference between collapsing under the strain and surviving or even thriving in new circumstances.

Audience for Reprisals

Reprisals are only partly directed at the whistleblower. The more important audience is other employees, who receive the message that speaking out leads to disastrous consequences.

Snowden has provided a different, somewhat more optimistic message. He showed that the NSA is not invincible: its crimes can be exposed. He showed that careful preparation and wise choices can maximize the impact of disclosures. He stood up in the face of the U.S. government, and continued unbowed. Although few whistleblowers will ever have an opportunity like Snowden, or take risks like he did, there is much to learn from his experiences.

Author

Brian Martin is professor in the School of Humanities and Social Inquiry, University of Wollongong, NSW 2522, Australia, and vice president of Whistleblowers Australia. Email: bmartin@uow.edu.au.

Full article:

http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=6969194

JOIN SSIT

JOIN SSIT