Rutgers University Press

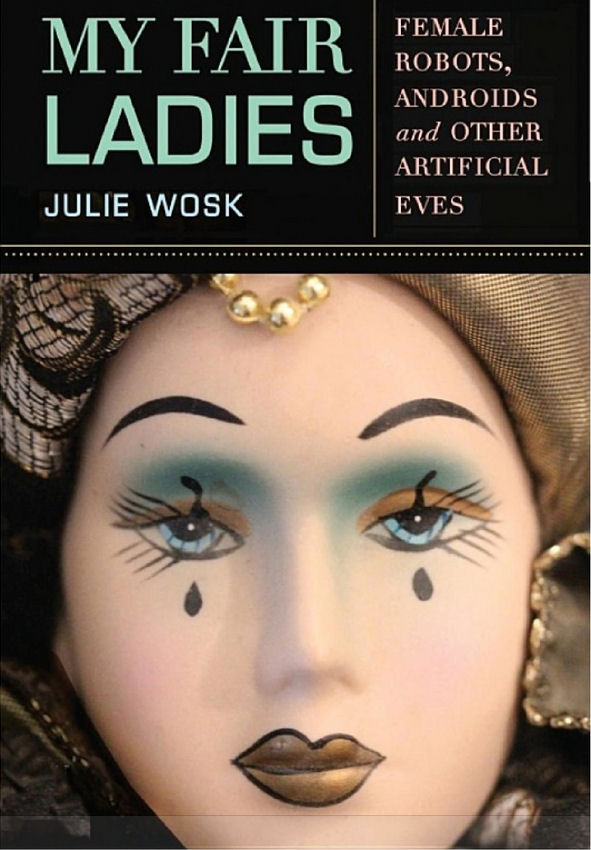

Rutgers University Press My Fair Ladies: Female Robots, Androids and Other Artificial Eves

By Julie Wosk. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2015, 221+xi pp.

Julie Wosk’s My Fair Ladies is an engaging historical account of female automata, with sidelights on dolls, disembodied electronic female voices, masks, make-up, and the sexual and gender implications of efforts to create artificial humans. Wosk focuses mainly on the Western cultural context, although recent Japanese and Korean explorations of the female-robot theme are presented toward the end of the book. The impressive filmography serves as the archival database from which she draws, along with citations to many works of art. Some print sources are cited as well. There are numerous black and white illustrations, and a very welcome and well-chosen section of color plates.

Little beyond congeniality and good looks were expected of female automata, whereas male robots more often were assigned technical capabilities and competences.

Wosk’s narrative takes us from the Pygmalion myth of antiquity through 17th century images of women made of household utensils, to full-size 21st-century dancing pink “plastic-fantastic” Asian female robots with Mickey Mouse ears. Along the way we learn much about why so many real and fictional creators of artificial women are, like the prototypical Pygmalion, men haunted by techno-erotic fantasies of creating the perfect woman. A significant component of this historical phenomenon is that there have been very few women clockmakers, engineers, and sculptors to design and build male automata for any purpose, let alone for the fulfillment of romantic fantasies. Most fictional designers or imaginers of artificial male humans, including Frankenstein’s monster, as Wosk points out, have been males themselves.

Consistent with the book’s title, male automata are not a major theme, although a few are mentioned for gender contrast. Wosk makes the point that in most of the cases she examines, little beyond congeniality and good looks were expected of female automata, whereas male robots more often were assigned technical capabilities and competences. Mindless docility, loyalty, and selfless helpfulness are the dominant characteristics of Wosk’s historical artificial women, with the Stepford Wives movies being, of course, a notorious example. Both the 1975 and 2004 films by this title are discussed in detail. It is, significantly, the humanity missing from these engineered females that seems to make the fantasy of them attractive to their male creators. They do not nag, criticize, or argue; indeed, many cannot talk at all. Wosk presents an amusing historical counterexample, however, in the “Rights of Women” automaton, manufactured by Renou in 1900.

Wosk devotes a few pages to female sex robots, including, delightfully, one with a snoring feature.

As Wosk points out, the caring and nurturing aspects of women’s traditional roles are occasionally included as fictional characteristics of female robots and androids, as in the case of Rod Serling’s robot grandmother in his 1961 Twilight Zone episode, “I Sing the Body Electric.” These and a few other examples in My Fair Ladies prefigure contemporary Japanese efforts to produce caregiving robots for the elderly.

Another appealing quality of many of these “virtual women” to their designers and/or owners is that, unlike real women, they can be turned on and off at will. Star Trek Next Generation fans will recall the 1990 episode “The Offspring,” in which the android character Data’s daughter’s “off” switch is activated when, like real human children, she asks more questions than the adults care to answer. Not all of Wosk’s artificial women lack autonomy, however; some of the fictional female automata go radically out of control, not infrequently in sinister ways. Female agency is also the major theme of Wosk’s brief but intriguing discussion of women’s uses of make-up as masks to make themselves appear to be ideal women, creating themselves as works of art. Wosk’s account recalls the late Pittsburgh-based artist Suzanne Marie Steiner (1937-2016), who, when asked in 1974 how wearing makeup was consistent with her feminist stance, replied “I’m an artist. Nobody’s going to tell me not to paint my face.”

Also, on the theme of female agency, Chapter 7 addresses the issue of “The Woman Artist as Pygmalion,” about the creation of artificial women by real ones. In the same chapter, Wosk addresses the recurring cinematic and literary theme of disembodied or separated artificial parts: male, female, and neither of the above. Some of what she says of this motif resonates with social psychologist and feminist Dorothy Dinnerstein’s (1923-1992) hypothesis about the incompleteness of both sexes under the regime of traditional gender roles — neither sex, in Dinnerstein’s account, have a complete inventory of human emotional and intellectual parts (The Mermaid and the Minotaur, Other Press, 1976, reprinted 1999).

On the dark side of feminized robotics, Wosk devotes considerable attention to Masahiro Mori’s concept of the “uncanny valley,” which she defines as “that psychic place where someone discovers that what looks animate is not really alive.” She points to evocative historical examples of male horror when they eventually confront the “thinginess” of their robots. She develops this theme in depth in Chapter 6, which is entitled “Dancing with Robots.”

Dancing with female automata, Wosk points out, is a frequent historical theme, possibly because of the cultural tendency to interpret partnered dancing as “a vertical expression of a horizontal desire,” as the aphorism attributed to Robert Frost has it.

There are a few unexplained omissions from Wosk’s otherwise-encyclopedic account of artificial women in Western history, most notably inflatable erotic dolls, and that ultimate lost icon of bizarre romantic fantasies, the Alma Mahler doll created in 1919 by Hermine Moos at the behest of Alma Mahler’s former lover, the Austrian artist Oscar Kokoschka (1886-1980). The absence of the pseudo-Alma from My Fair Ladies seems especially odd because it perfectly fits one of Wosk’s themes: the creation of a female simulacrum by an initially infatuated male, who then destroys his creation when it fails to live up to his ideal of womanhood. Her paradigmatic example of this is the chief female protagonist of the 1870 ballet Coppelia and its 1900 silent film version.

Although the inflatables are missing, Wosk does devote a few pages to female sex robots, including, delightfully, one with a snoring feature. Erotic dolls have been addressed recently by other authors, notably by Anthony Ferguson in The Sex Doll: A History (McFarland, 2010), and Marquard Smith in The Erotic Doll: A Modern Fetish (Yale University Press, 2014). Wosk may have decided that this ground was already successfully covered, although neither work is cited in My Fair Ladies. The “Betsy Wetsy” doll of the 1950s is also conspicuous by her absence, although there is a good, though brief, discussion of the talking dolls of the 1960s.

Throughout the book, a hard-core technology fan might wish for more nuts-and-bolts attention to the technologies involved, but Wosk has an illuminating command of the aesthetic and psychological elements of her history. Some of the film plots she describes are difficult to follow, but as any viewer of science fiction movies can confirm, this is almost certainly an artifact of the convoluted and frequently confusing plots themselves. Because Wosk’s account is partly chronological and partly thematic, the narrative sometimes moves back and forth in time.

Wosk’s innovative and readable approach to gender and technology issues in history might make her book a provocative supplementary text for courses that address gender and sexuality in a technological and scientific context.

Reviewer Information

Rachel Maines is a member of the Columbia University Seminar in the History and Philosophy of Science. She is the author of The Technolo-gy of Orgasm, Johns Hopkins Uni-versity Press, 1998. Her email address is rpmaines@gmail.com.

JOIN SSIT

JOIN SSIT