A concept that seems to arise in discussing how to attract technology experts, or bring young people into technology fields, often devolves into discussions of salaries, taxes, and even cost of living. The underlying assumption is that techies, including engineers, are motivated by money. My experience indicates that this is a false assumption, often a result of executives or economists projecting their own theories on folks with a different perspective. Engaging the right talent, and targeting the right objectives are the keys to motivating change, but in few cases is it money.

Some of the big names in high tech seem to be some of the richest people on earth, or at least well up there. This is particularly interesting when they are the founders of the related company. But when you look more closely you find these are the individuals that identified how to monetize a technology, not always the engineers that created it. Bill Gates was able to implement Dartmouth Basic on one of the first hobby computers, then on to other platforms. He acquired an operating system that became MS/DOS. He hired folks to build or purchased versions of technology for word processing, spreadsheets, etc., all of which were created by others first. Techies like Dan Bricklin and Bob Frankston, who invented Visicalc, never reached that level of visibility or financial standing.

Engineers and techies solve problems. Sometimes they make money. It is solving the problem that is a key factor. One of my favorite jokes is set in the French revolution, one morning at the guillotine. The first person that day was a priest. When the device failed he claimed “it is God’s will, you must let me go.” The second was a lawyer. When the rope was pulled the blade once again failed to fall. “The law says you only get one try, you must let me go.” The next was an engineer. He looked up and said “I see the problem, the rope is caught on that pulley.” It is a painful truth that techies fail to see what is in their own best interest and are delighted by finding solutions.

Our world is in a rapid transition driven by technology. Organizations who want to contribute to the changes, take advantage of the changes, or at least try to understand the changes need technologists. The technologists are often not the ones that know how to maximize the profit to be generated by their innovations. They are rarely assertive enough to seek compensation that is commensurate with their contributions. It is not the higher salary or lower tax rate that will draw them in. They want to solve problems.

How do you motivate change, and the technologists that make it happen?

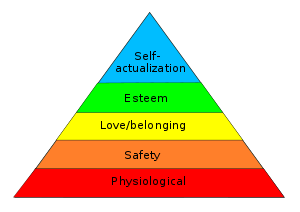

Maslow’s heirarchy of needs. (Wikipedia)

Techies like to have their basic needs met — food, water, security, etc. All of the things at the bottom layers of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. All of the other layers apply as well, and you will notice that these are love and belonging, esteem of self and others, and self actualization. Money is not on the list. The more recent take on this by Dan Pink in his book “Drive” identifies three key motivators: autonomy, mastery and purpose. Again money is missing.

Some of us idealists want to change the world: “for the benefit of humanity” as IEEE has in their current tagline. This is purpose, actualization, a path to the esteem of colleagues and beyond. This purpose holds true if you look at the factors that drive the Open Source movement with it’s millions of contributors worldwide and massive impact on our systems with Linux, Apache servers, and Hadoop, and this list goes on. These techies are not getting rich doing this, they are solving problems and gaining the esteem of their peers.

Innovation will not die for the lack of financial incentives. Techies do not need to live in cultures that generate massive financial rewards. They do want to be able to solve problems, and that requires some degree of freedom. But the restrictions on this freedom are as likely to come from short-sighted management than repressive governments. Do you want to attract the best people? Give them a problem with a purpose. Give them room to work. Give them recognition for their successes — not just internally, but encouraging them to share these at conferences, or in relevant peer communities. And yes, give them some money too, perhaps even commensurate with their contributions — which can be significant. They may not ask for it, but they may recognize that this is the way the “monetizers” show their recognition of a job well done.

JOIN SSIT

JOIN SSIT