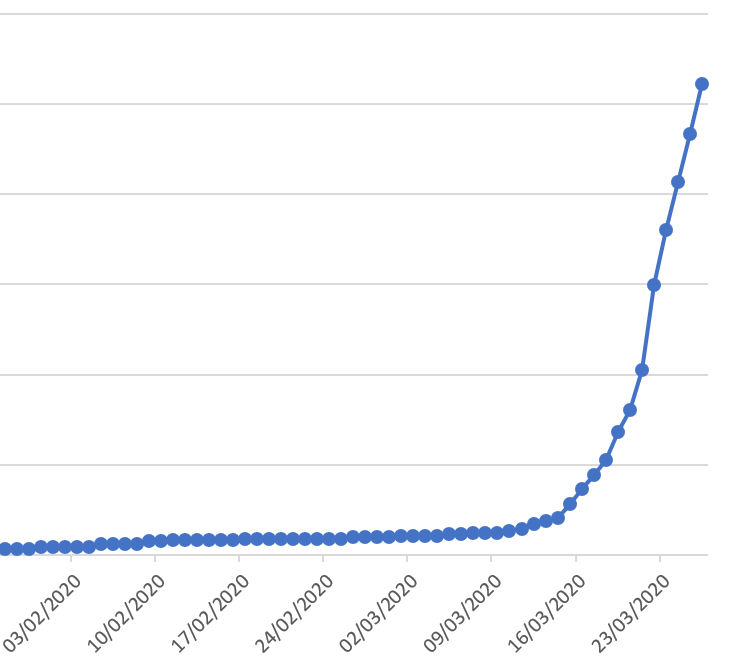

COVID-19 Graph as of 2020-03-26 in Thailand. Wikimedia Commons/Bennypc

COVID-19 Graph as of 2020-03-26 in Thailand. Wikimedia Commons/Bennypc The transcripts that follow speak to the potency and promise of dialogue. They record two in a continuing series of “COVID-19 In Conversations” hosted by Oxford Prospects and Global Development Institute (OPGDI), an interdisciplinary research center of Regent’s Park College, University of Oxford. Dedicated to promoting discussion and inspiring new ideas on the development of China-U.K. relations in the context of globalization, OPGDI is exceptionally positioned to illuminate the comparatives and commonalities in East/West perspectives—in times “normal” or “unprecedented.”

This fiercest public health crisis in a century has elicited cooperative courage and sacrifice across the globe. At the same time, the COVID-19 pandemic is producing severe social, economic, political, and ethical divides, within and between nations. It is reshaping how we engage with each other and how we see the world around us. It urges us to think more deeply on many challenging issues—some of which can perhaps offer opportunities if we handle them well.

This fiercest public health crisis in a century has elicited cooperative courage and sacrifice across the globe.

The conversations transcribed here come within the scope of OPGDI’s ongoing projects on the theme of “Technology-Society–Ethics,” engaging academic audiences at the intersections of technology with social management widely and higher education specifically. In the first, ethicist Dr. Mariarosaria Taddeo and engineer Prof. Jeremy Pitt, moderated by lawyer Prof. Shuangge Wen, confer on the use of technology in epidemic response management, and the diverse, often disputed, ethical, legal, and social considerations this raises. Shadowing the practicalities and politics of the technology-enabled coronavirus control measures of the past year is the spectre of privacy diminished and lifestyles dominated, for motives good or bad. The speakers’ discourse highlights the key need for trust in institutions and the vulnerability of values, as well as lives when biology or technology “goes viral.”

In the second conversation, educationalists Dr. Lynn Robson of Oxford University and Prof. Hua Sun, assisted by Dr. Fang Wang, of Peking University, moderated by OPGDI Director Dr. Shidong Wang, address the practicalities and prospects of blended learning models within their university settings. Their accounts of firsthand experience clearly demonstrate the ways that an institution’s scale and style of pedagogy shape its application of standardized technological tools in adapting to dramatically altered conditions. Their conversation resonates with the immediacy of steep learning curves—for teachers as much as students—and the shared human impulses, as well as culturally distinctive characteristics, within technological inventiveness.

The pandemic urges us to think more deeply on many challenging issues—some of which can perhaps offer opportunities if we handle them well.

Framed within the current pandemic, these conversations transcend its transience, exploring the deep and enduring linkages between material and intellectual forces as well as between cultures and nations.

Author Information

Louise Gordon is a Publications Manager for Oxford Prospects and Global Development Institute (OPGDI), Regent’s Park College, Oxford University, Oxford, U.K. Contact her at pa_opgdc@regents.ox.ac.uk.

____________________________________

Some Ethical, Legal, and Social Dimensions of Pandemic Response Technology

Shuangge Wen, Mariarosario Taddeo, and Jeremy Pitt

Shuangge Wen (SW): The test and trace systems in operation in many countries are a key strategy to lower the reproduction rate and control the virus, with technology enabling measures such as tracing of close contacts, notifying local alerts, and venue check-ins using QR codes. From your technological expertise, how do you see these systems working, and do you see any alternatives which should be explored?

Mariarosaria Taddeo (MT): In my work, I’m most concerned with the ethical and social implications of these kinds of technological interventions. When the first app was about to be released, the Digital Ethics Lab (in which I serve as Deputy Director) focused on what are the requirements that these kinds of apps need to respect to ensure that they will be ethically sound. For these apps, being ethically sound is important because, as we saw with the failure of the first app if citizens do not deem the app ethical, they do not trust it and do not adopt it. In this case, the efforts, funds, and time invested in developing the app will turn into missed opportunities; in turn, this will hinder government reputation. So, ensuring that these apps respect fundamental values and rights (i.e., are ethically sound) is vital.

In a paper published in Nature [1], we identified a number of requirements to be respected by these apps. The key point here is that these apps pose a tradeoff between public health and individual rights—for example, balancing privacy and tracking of one’s whereabouts. This kind of tradeoff is not impossible to achieve, because whilst privacy is a fundamental right, it is not an absolute right. Thus, you can have more or less privacy. This is shown, for example, in the GDPR, which makes provisions to limit individual privacy in order to ensure things like public health or public safety.

In this context, how do we strike the right balance between competing rights or interests?

So, in this context, how do we strike the right balance between competing rights or interests? The first dimension is necessity: Do we know that this app is a measure without which we cannot find a solution for saving lives? If the answer to this question is “no, there are other solutions” or “there are better solutions,” this trade-off fails at the first requirement and we shouldn’t proceed further.

The next question is: Does this app offer a proportionate approach? In other words, are the limitations to individual rights that the app poses functional to achieving greater benefits for individuals and society? Now, we can move onto the third question: Is the solution offered through this app sufficiently effective, timely, and accurate? Is there scientific evidence that this solution, for all its costs, is going to work? Where there is no scientific evidence, the answer to this question is problematic.

Finally, if the app is justified by the gravity of the current situation and if it poses important limitations to individual rights, it should be adopted as a temporary solution. This means that there has to be an explicit “sunset clause,” i.e., an explicit statement of the moment, or the conditions, for deciding to discontinue the app.

Jeremy Pitt (JP): In the U.K., we’ve had two versions of the NHS test and trace app. The first version failed for at least four reasons. First, because they were trying to apply a technology that hadn’t been used in this way before—that was the use of Bluetooth. So, there was unfamiliarity and inexperience. Second, there was this sense of “not invented here,” so they ignored the existing infrastructure on which to build a solution. Third, they went for a centralized solution, rather than, for example, storing information on the phone. Fourth and finally, to my mind, they ignored the human element of this upon relying on self-diagnosis rather than robust testing. From an engineering point of view, this amounts to not understanding the nature of the human beings involved in the technological loop.

In the second iteration, they addressed a number of these problems, but are still relying on Bluetooth, which remains an unproven technology for doing this kind of thing. This reduced the focus down to the unit of encounters, which meant trying to work out infection risk from the signal strength and the length of exposure to that signal strength. But these are only two of many factors; there is also the density in the location, and the ventilation in the location, and many other factors that we don’t actually know about how the virus is transmitted.

This gives us three problems: One is the risk of false positives. A second problem is the risk of false negatives, and as Mariarosaria points out these are absolutely crucial to know that the technology is working as it should. Third, this app should not be seen as a “silver bullet” solution, but as just one tool in our toolbox. Location tracking via an app has to be complemented with robust and reliable testing methodologies; it has to be complementary to public health messaging about social distancing and mask wearing; and it has to be complemented by human-led contact tracing, which is what happens after you’ve identified the contact. And ultimately, you cannot see this process as being punitive. Having detected that someone has been exposed, you’ve asked them to self-isolate, but after that the state has got to provide them with the appropriate financial support, the appropriate emotional support, and the appropriate logistical support to ensure that the time they spend in isolation is actually effective. Without these social supports, any test and trace technology is going to be ineffective.

Looking further ahead to subsequent iterations, public trust is not going to be invested in the widespread adoption of contact-tracing apps, which will be needed to cope with new outbreaks caused by virus mutations, if updates are blocked because of privacy violations [2].

What we call a “digital solutions technology” is a mere tool—it does not work without a strategy.

SW: Your remarks resonate with my own field of law, where we are keenly aware of the discrepancy between the law in books and law in practice, and it seems the same thing occurs with technology! Each of you has mentioned the importance of the human element, in public attitudes and support towards the adoption of this kind of technology, with its effectiveness in real-life affected by contextual factors. Would you elaborate a bit more on the social or pragmatic factors affecting the acceptance and effectiveness of these test and trace mechanisms?

MT: One important point involves a key word that is sometimes abused in the public discourse, and that is “trust.” There can be an assumption that citizens trust the technology and trust the government, and that’s true, but only up to a point. We forget that trust is something that has to be earned, rather than just obtained by default. When a government issues a digital track and tracing technology, it is leveraging a great deal of trust from its citizens, and especially in democratic countries, leveraging that trust cannot come without accompanying “guard rails”—such as explicit transparent governance of the technology.

In the case of the first version of the app in the U.K., this was not the case, because as Jeremy pointed out, there was a focus on a centralized approach with refusal to rely on solutions already used in the EU. There was a lack of transparency on how these data were going to be managed, with a top-down approach, deaf to the values, and respect that public opinion was pushing for. That contributed to the failure of the app.

There is a second element, which is the digital divide. Jeremy mentioned that we look at technology as a “silver bullet”; what we call a “digital solutions technology” is a mere tool—it does not work without a strategy. Track and trace was a great opportunity, but you need to account for a country like the U.K. having a digital divide in which access to digital technology is limited for rather big parts of the population. Some people still have old versions of mobile phones which can’t download this app. A recent report shows that a considerable proportion of the population—those aged over 65—have very limited digital skills; for them, downloading an app would be a very difficult task. For the same part of the population, it June be hard to have a clear sense of the relevancy of this app, its limits and benefits.

JP: From my point of view, complementing those social and contextual factors, there are some political ones. Essentially, these are down to structural weakness due to an emphasis on an ideological form of government that holds the commitment to centralization rather than regionalization. The need for local government to be involved in the decision making and the implementation has been clear from the start, but those actors have been underfunded and cut out of the loop. There’s a tension between outsourcing everything to private organizations versus engaging all stakeholders. We don’t have corruption in the U.K., but we do seem to have an awful lot of “consultancy.”

Another dimension is what happens in a country that has experienced a lot of, largely manufactured, culture wars. These arguments over conflicted cultural issues mean that the wearing of face masks isn’t interpreted as a matter of public health but taken as a marker of which side of a political divide you’re on. We have a real breakdown in the relationship between the demos—the people—and the rulers. We have a government that is deliberately exploiting and polarizing divides, with the result of alienating half the population, when what this crisis requires is buy-in from the whole population. Separating your appeal by voter segments disables the collective action which is most called for.

Finally, we are experiencing a complete lack of accountability, without responsibility being taken for mistakes. One of the founding principles of democratic regimes is the ability to “fail forward”—as in the saying that all political careers end in failure. Well, you could say the same thing about all political regimes. The key component of failing forward is that you learn from those mistakes, that is what gives you systemic improvement. But where a government is in denial about the mistakes it has made and seeking to blame everyone else for what went wrong, including the public whose buy-in you need, well, this is just a recipe for systemic failure.

SW: Following on from Jeremy’s remarks about the politicizing of this crisis, some of the most heated debates in relation to this pandemic are about balancing health with the economy, and this is often presented as a binary choice, as a zero-sum game. Responses to the pandemic are often framed in terms of striking a balance between differing values and priorities. How can we maintain or strike a good balance between the effective use of these test and trace mechanisms, alongside the protection of citizens’ fundamental rights, such as data privacy?

MT: As I was saying before, the first step is to understand that such a balance is feasible. We must recognize that privacy is a fundamental right, not an absolute right, and we already have regulations that acknowledge this balancing. In the case of this pandemic, the balancing includes the readiness to revert towards greater privacy when the pandemic ends. And it requires having appropriate measures to revert to the status quo ante, like mechanisms to ensure accountability, as Jeremy pointed out.

These measures are important to show that the limitations on rights that the apps pose are meant to be temporary and proportionate, and that they are motivated by the need to address the crisis and would not pose medium- or long-term hazard for our democracies. These measures include full transparency of processes and fundamental accountability, so if something goes wrong, there won’t only be a punishment to those who made a mistake but also an understanding of where and how the mistake happened, and how not to repeat it. This provides a means of learning and improving, with a clear understanding of the benefits we want to achieve and the strategy for getting there.

Taking as an example the first version of the app, one of the reasons put forward for not using a more distributed approach was the epidemiologists’ need for data collection. But then the epidemiologists themselves said, in fact, these data are not sufficiently clean and they’re not so relevant insofar as they rested on self-diagnosis rather than a test. Citizens should be given the reasons why a specific technical solution is designed in a certain way, and that reasoning should stand up to scientific proof, ethical, and legal scrutiny. Each of these is an important component in undertaking what is a multi-dimensional task. It’s not simply “privacy versus the pandemic”; rather, it’s individual rights, in the context of a pandemic, with respect to the power of a government. It’s a complex task, requiring much refinement and fine-tuning. But it is workable and can be achieved.

JP: I agree with that entirely. There is an attitude that complex problems can be reduced to simplistic solutions, which becomes hugely problematic in the messaging. This issue of balancing extends beyond test and trace to what happens afterward. Vaccination is one potential medium-term solution. However, we already have a strong anti-vax movement, and this is one of the biggest dangers, especially given the lack of accountability and transparency. The most damaging outcome will be if take-up is limited to 70% or 80% of the population, leaving the virus to spread among those not vaccinated and then mutating and reinfecting those already vaccinated.

Here, we see the downside of failing to communicate properly common knowledge and the public good, and it becomes a matter of civic education and civic dignity. Public health is necessarily about balances and tradeoffs, and it must be understood that vaccination in this pandemic is about an individual’s rights versus a public good, and it is imperative to suppress your individual concern for the public good and get vaccinated. Your right to swing your fist stops at the point that my nose starts! This is something philosophers and ethicists have discussed for centuries. Alongside the development of technology, there must be reliable civic education; dealing with a pandemic is not just a technological solution, but also an educational one.

SW: Picking up on that point concerning education, the U.N. secretary general has pointed out that a key cause of poverty and inequality is limited access to digital technologies, with millions, perhaps hundreds of millions, of vulnerable people being left behind as our lives increasingly move online. What ways do you see to expand digital access and to protect the most vulnerable, both during and after this pandemic?

MT: There are a few ready answers to that very deep question. There is a considerable need to expand access to the hardware, and then to improve the level of digital literacy to make use of it. But, we shouldn’t think that the responsibility to overcome the digital divide rests only on the government; there is a part for civic society to play. Here in Oxford, as elsewhere, COVID-19 mutual aid groups have arisen, linking people who possess digital literacy and expertise to those without. That’s an approach worth leveraging because it’s one of the most immediate and direct in the time of a crisis. Especially when using a digital device is necessary not only for track and trace but also for online grocery shopping, talking to friends and family, paying your bills, communicating with your doctor. These services are especially essential for the weakest segments of the population.

JP: Again, I completely agree, and would only qualify Mariarosaria’s remarks by saying that you don’t only have to encourage civic responsibility, you have to empower it as well. From a socio-political standpoint, yes, you have to put government online, but you have to put people online as well. The trust flows both ways: the people need to trust the government, but the government needs to trust the people sufficiently to empower them to undertake local organizing and community building, activities that have been woefully neglected.

In engineering, there is a development methodology called value sensitive design, and I think this complements the ethics which we have been exploring. The idea here is that you’re not building a system just because you want it to do some kind of function, but there’s also a qualitative human value that you seek to promote, and the point of value sensitive design is to put those values as primary design requirements alongside the functional and non-functional requirements normally specified. We really need to encourage this approach to design, not least for protecting vulnerable groups.

There are two things here to be concerned about. First, the notion of the public interest. We need the technology which is informed by value sensitive design so that we can start building systems that empower people to understand and take control of matters of public interest. This means making it clear to people what problems are trying to be solved, how these affect them, why the technology is being introduced, and why decisions are being made. This pulls us back to accountability and transparency.

Second, I fear that a huge mental health crisis is being stored up during this public health crisis. Technology companies try to get people hooked on using their products. There’s this notion of addiction by design in gambling, with designers examining what techniques in digital systems incline people to continue to gamble. Some of these techniques have been picked up and applied in getting people to use their devices and apps more generally, and this will have been exacerbated during the pandemic with people spending more time online. You can liken this to the recovery from “Long COVID,” where people have long-term symptoms. We are going to have to deal with this problem too, in particular, protecting vulnerable groups, among them the younger generation which has moved their lives almost entirely online, interacting through screens with their formation of social relationships disrupted and having their education and employment prospects disrupted. These people will need sensible, constructive solutions, and support.

SW: I would like to wrap up with a word and theme which both of you have powerfully highlighted: trust. How do you foresee technology during this pandemic affecting and transforming substantive qualitative human values such as trust?

JP: There are many initiatives that can be looked at in this regard [3]. For instance, there’s the concept and practice of design contractualism, where engineers make ethical choices and encode them in the system, and their ethical decisions are then made visible in the interface. This harks back to Tim Berners-Lee’s initiative in linking data to give people far more control and ownership over their own data. I have seen mention of a kind of Hippocratic Oath for ICT practitioners and also a very interesting article by Luccioni and Bengio (a winner of the ACM Turing Award), on making moral choices about the use of deep learning and applications of artificial intelligence [4].

Then there’s the whole issue of informed and meaningful consent—the pretence that when you make one of these contracts you have actively read and understood the terms and conditions. We can turn this on its head to say: you know these are my rights and you have to respect them, not just for privacy but also for attention, and for the data itself, and for knowledge not only of who is stipulating something but where do they get it from. My own technological solution to this is called PlatformOcean [5], where we’re trying to empower communities and make sure they can keep all their own data within the platform.

Then there is an exploitation of the automation bias, and this is distinctly problematic when you get complex situations, such as when people start delegating cognitive skills to the machine. We see this with voice-activated video assistance. The generation growing up with these starts “outsourcing” to Siri or Alexa, rather than relying on their own mental capacities. This might be okay when the question is “Siri, what’s 4+4?” But it starts becoming more problematic when your question is “Should I get vaccinated?” or “Who should I vote for?” This exploits the automation bias in a way that can undermine an individual’s decision-making skills and can become manipulative.

MT: Artificial intelligence and digital technologies, more broadly, have great potential to improve our lives. Indeed, they are already improving our lives: we can work, we can get educated, we can talk, we can develop science much better than we could have without digital technologies. Having said this, these technologies are coupled with serious ethical risks: lack of transparency and accountability, and disparities in access to and the ability to control these technologies are good examples of these risks. Risks also come from the over reliance on AI and digital technologies. This is problematic, insofar as AI-based or digital solutions are not necessarily the optimal ones in all circumstances, and they always pose important ethical challenges. So, in some cases, relying uncritically on these technologies June have a negative impact on rights and values, while not leading to an effective solution.

My second point is about trust as a concept in itself. Trust is an easy word that refers to a very complex concept that philosophers, psychologists, ethicists, economists, and cyber-security experts consider in divergent ways. But there is a common element. At a high level, trust is a way of delegating a task and choosing not to control how the task is performed. The lack of control is important here; it is what makes trust a facilitator of social interactions. For instance, I don’t control how a doctor makes a diagnosis about his or her patients; I delegate the task, in that way saving time and energy to do my own job. And you can imagine this occurring for very many functions in society.

There is a risk though, that with this relationship between the lack of control and delegation if there is too much trust in a society, we lose accountability because you lose any chances to perform control. Yet, if there is too little trust, the system doesn’t work because you have to check everything. So, there is a balance to be struck.

There is a further element to trust, which is realizing what is the trustworthiness of the trustee. This is your assessment of the agents in whom you decide to place your trust. Some of the literature merges this with the concept of reputation: the idea that someone has been able to perform that task to date, so they will be able to perform that task going forwards. However, the assessment of their trustworthiness does not only depend on the reputation of the trustee, but also on the risks that one takes if the trustee does not behave as expected. Assessing this risk is a responsibility that stays with the trustor (the one who decides to trust).

So, on the one side, trust is earned with a good reputation; on the other, trust is given on the basis of a risk assessment. Thus, those who decide to trust also have a responsibility to understand the risks that they take when trusting. In this sense, when we consider daily decisions to trust—from trusting a specific news outlet to voting a representative into our parliaments—there is a responsibility to make informed decisions and not to concede trust too easily.

Panelist Information

Shuangge Wen is a Professor and the Vice Dean with the School of Law, Jilin University, Changchun, China. She currently holds positions in a number of international academic institutions, including the Director of the China Commercial Law Academy, the China Security Law Academy, a member of the European Association of Law and Economics, and the U.K. Higher Education Academy. Her research specialism is within corporate law and corporate governance, and further extends to general aspects of business law and interdisciplinary subjects including business ethics.

Blended Learning: New Prospects for International Higher Education

Shidong Wang (SW): Please share with us the pandemic experience of Peking University and Oxford University. How has your university adapted its education and teaching to COVID-19 conditions?

Hua Sun (HS): Both university campus closures and economic stagnation have had major impacts on higher education. Over the past months of COVID-19, online teaching has become the main teaching method for colleges and universities globally. This pandemic scenario has necessitated teacher training programs on how to conduct successful online teaching under unprecedented pressures and challenges all within a very short time. And of course, such programs can take place only remotely, with teachers having to support students and their parents alongside.

We believe that online teaching can, to some extent, make up for the loss of in-person teaching and learning, but economic, technological, and educational levels differ greatly between campuses in China. For this reason, the Ministry of Education in China has announced that all schools and universities should coordinate, at both national and local levels, to bring in the rich quality of online education resources and the other support and services for continued learning available across all regions.

Here at PKU, we have been offering 4000 courses by 3000 teachers online. We are very pleased that through cross-disciplinary and cross-department coordination, these courses have been delivered in consistency with their learning goals, and it is encouraging that some teaching performance has even been improved by adopting innovative methods. Many teachers felt quite nervous and anxious at the very beginning about the new method, having never tried online teaching before. To ease their pressure, our Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning has been providing training sessions, not only on technical tools, but also on teaching methodologies and strategies for the purpose of improving student interaction and online learning experience. We have also set up a hotline information mailbox and We Chat group to provide extra support.

We offer online education in five modes: live-streamed lectures, pre-recorded lectures, massive open online courses (MOOCs), webinars, and studio lectures for the best possible outcome equivalent to the on-campus experience. Most undergraduate classes are delivered through live stream or pre-recorded lectures, while postgraduate courses tend to be taught in smaller size classes so that one can have more diverse formats. We have found that the use of multiple modes is conducive to better learning results.

Online teaching will continue to play a very important role even after the pandemic.

Our training courses to faculties and departments have also covered an online examination system, with a technology solution that supports the necessary system security and stability. Postgraduate research proposal presentations and thesis defences have also been successfully conducted online.

Actually, teachers are surprised to discover that hybrid online/offline modes can be no less effective, so With our growing experience of online teaching, we have identified its constraints and started making some changes in course design, software, and technical support. As online teaching becomes more widely accepted, we anticipate that teachers will be able to use blended teaching methods effectively, with continual improvement in the teaching and learning experience.

Lynn Robson (LR): Here in the U.K., when the first lockdown came into force, it was at the very end of the second 8-week term of Oxford’s university year. In some ways, this was fortunate, as it gave us the vacation break to prepare for students’ return in April. This did mean that we were working flat-out during the period when we would normally be researching and recuperating. So, it was a great deal of work within a very short span of time.

As Oxford is a collegiate university, we have students in about 40 colleges located across the city. For undergraduates, their college isn’t just a dormitory or hall of residence, but where all their teaching and learning is organized and delivered. The University’s faculties and departments have oversight of that, but they aren’t involved in the day-to-day teaching for a lot of the students. They do, however, provide large-scale lectures, and these all immediately moved online, so a very similar arrangement to Professor Sun’s description of modes and technologies used at PKU. And as at PKU, our Centre for Teaching and Learning was intensively involved in educating faculty members in the practicalities of online lecturing, providing guidance, and support for people who had never had to record a lecture previously.

While this was happening at the university level, within the colleges it was a bit different. At Oxford, college teaching is based on the tutorial system. This is a weekly meeting between one to three students and their professor, so it is uniquely adapted to moving very swiftly online because all we need is the technology and we can carry on teaching a tutorial much as before. For us, the big challenge was having all our students dispersed into their homes and guiding them and the staff through that change.

A big concern for our students was access to library provision. The tutorial system is based on independent learning; the tutorial happens once a week, and between those contact hours, students are expected to pursue their studies independently. Students were very concerned about how they would get hold of all the material that they needed in order to do their studies. This became a huge task for the library staff. Oxford University has the Bodleian, which is a copyright library serving the whole university. Then, each department and each faculty has its own library, as does each college. How were we going to make these resources in all these places easily available to the students, so that they could carry on with their learning even while they were at home?

So, although the ability to teach a tutorial online was pretty straightforward, the kind of support the students needed was far from straightforward, and I have to say that coordinating that effort between faculties’, departments’, and colleges’ libraries, plus laboratories and so on, was a complex and time-consuming process. Thankfully, there was a lot of cooperation at every level.

Trinity Term, which is the final term of Oxford’s academic year, is a bit lighter when it comes to teaching because two-thirds of our students are undertaking examinations. Now, that presented additional complexity and challenge because examinations are overseen by the University, and each faculty and each department impose different requirements and needs for their particular examinations.

At the college, our job became guiding our students through that process, acquainting ourselves as teachers and directors of studies with how the examinations were going to run, what format they were going to take, and then guiding our students through that. As colleges, we had to prepare our students for a very different kind of examination from what they were expecting, and we found ourselves communicating with our students individually about what their technological capabilities were.

We were very concerned about the widening gap between the most advantaged and the most disadvantaged of our students, in terms of what level of secure and stable access they might have to the internet, and what that might mean when they came to sit their examinations. Working closely with our faculty and department colleagues across the university, we developed a robust system for considering mitigating circumstances when it came to finalizing examination results so that students would not be unfairly disadvantaged by moving exams online.

I must say that this was all a very steep learning curve not just for our students, but for us as teachers as well. Not only adapting our teaching to being online but also making sure that we were understanding our students’ needs and their anxieties, so we could best support them. Reflecting on my own first experience of teaching an online seminar course, I found myself facing a virtual room full of students whom I had never met before, and I couldn’t see them because cameras had to be kept off due to bandwidth limitations. That felt particularly challenging to me: How do you form a relationship with a group of students you haven’t met before, where our Oxford system is so strongly based on small group teaching and tutorials?

At this current phase, we have students back, which is great. Though the U.K. has recently entered the second national lockdown, the students are staying, as the government has said very clearly that students should reside in their universities not only for the sake of their education but also as a public health concern, to avoid students traveling back to their homes.

So, this term we have adopted much more of a blended approach, with a combination of in-person teaching—socially distanced and wearing face coverings—but also online teaching, and in some seminars using both simultaneously if, for example, we have students who are self-isolating. We have also been very cautious by allowing members of staff to decide for themselves whether they wish to return to face-to-face in-person teaching or whether they wish to carry on entirely online. We’ve made that a personal choice for individual members of staff because obviously everyone has their own concerns and household circumstances. So, it’s not just blended learning for the students, it’s also blended teaching for the tutors.

SW: Thank you both for highlighting so many of the dimensions of blended learning of hybrid online/offline modes. As a measure for coping with some of the immediate practical issues of the pandemic, such as self-isolating students. And equally, as a mode which is sometimes even preferred by teachers and students, and perhaps holds the promise of improved educational experience and results. I would like to consider this from the “other side of the coin,” exploring the aspect which you each also mentioned of some students potentially being disadvantaged when teaching moves online. How do you see these current developments affecting accessibility and inclusivity?

LR: That is a most interesting topic because this idea of inclusion and accessibility, and diversity in education was already under much consideration before the pandemic hit. It was regularly discussed in our college and faculty meetings: How can we be more inclusive? How can we enable a positive experience for our students with specific physical challenges or with specific learning difficulties, or those who are located overseas and in different time zones?

But, at the same time, the discussion was informed by the framework that such students were in the minority—that we were catering to the minority by recording lectures or seminars or similar measures. Suddenly, that’s become the majority situation; we’re all of us in some ways in need of special considerations; we all have specific learning needs.

Certainly, we all have challenges that have been presented by this new way of thinking about teaching and learning. The pandemic circumstances demand that, as teachers and institutions, we are much more creative in our approach to learning, to thinking about education and how we deliver it. In this, the pandemic has presented a really important opportunity. We’re all longing to get back to normal, but I think that this heightened awareness of the importance of inclusivity, of accessibility, of diversity in reaching out to others and minority groups within education, in particular, this awareness should be one of the most important things that we keep from this time.

The main concern we have is whether online teaching is as effective or as efficient as offline classes.

Fang Wang (FW): The main concern we have is whether online teaching is as effective or as efficient as offline classes. The online teaching platforms available in China are quite diversified to meet different teaching goals, and when integrated with different teaching tools or embedded within collaborative platforms, they are usually able to play their role with high effectiveness. The biggest remaining problem arises from disparities in internet connection and software and hardware availability among students.

Apart from Zoom and other online learning platforms, we have also established the Smart classroom, which enables students to attend the class either in the physical classroom or online from home. The professors can easily include these remote students to participate in the classroom discussions or presentations, working in breakout rooms and on digital blackboards to collaborate on projects. There are other add-on benefits, such as all students can access session recordings, giving students a better command of what has been taught in class in the physical classroom, and this will be of particular benefit for students who would otherwise fall behind.

We have also found that online teaching has improved self-study capability and as a result, improved learning outcomes. At Peking University, a survey found that the satisfaction rate was even higher than expected and quite a number of students suggested keeping the online teaching along with offline, after the pandemic.

Additionally, I think that online teaching has, to some extent, offered a solution to teaching resource imbalance and made sharing of the global academic and research resources possible. All of us have had the experience, during the pandemic, of enjoying more seminars or webinars and online talks in various fields, which was not very common before the pandemic. For education on campus, it seems online teaching will initiate a new environment of course delivery in which global collaboration will be embraced more actively in the future. So, I think these are all positive sides to these technology approaches within the education sector.

SW: Within the context of these technology- dependent classrooms, what do you see as the teacher’s role in stimulating motivated engagement and interaction from students, when lessons take place online?

LR: I think my task in this is a bit easier, because I am working with quite small groups of students, so it’s easy to keep them motivated. When you’re one-to-one with someone, they can’t be anything other than motivated, because there’s no escape! That said, even when I’ve been involved in much larger classes and assumed that the students might not be so interested, I’ve been pleasantly surprised by how engaged and how motivated they are. There has been an assumption that students will lose motivation online, but the experience I’ve had this year is quite the reverse, with very good attendance and lots of participation with students asking questions.

I give them the credit for that rather than for anything that I might actually do! Oxford’s tutorial system is based on the students themselves producing work; they have to write a paper every week, so the tutorial is dependent on student activity. This is a mindset which Oxford promotes in its students from the very beginning – that our students are active in their learning and they need to participate to make this work, that it’s not just about the teacher taking on the responsibility.

One of my key ideas as a teacher is that what I’m doing is building a relationship of mutual trust; my students need to trust me as a teacher: that I’m going to arrive ready to teach them, that I have a specific subject knowledge with which they want to engage. At the same time, I trust my students that they’re going to produce the work, and that they’re going to join in this conversation with me. Establishing that kind of relationship sounds as if it’s at the softer end of things, but in fact, it’s actually a very rigorous demand for a teacher to be making of students. That kind of initial engagement tends to keep students’ levels of motivation high, whatever the context and conditions, online or offline.

FW: At PKU, we are using Zoom, we are using Teams, and also Blackboard and Canvas, as well as our local teaching platforms such as ClassIn and Tencent. These platforms offer many different tools, such as a timer and dice, or we can give students’ trophies for their answers. We can share the students’ screens and deliver an individual board to each student for their answers, just like handouts in the physical classroom. Breakout rooms enable the allocation of students into smaller groups for discussion and then to come back to the main group.

All these interactive tools are easily accessible to the teacher and encourage collaboration among the students. It’s up to each professor which tools they want to use and how they want to use them, much in the way that ten years ago, teachers started to use Powerpoint or other multimedia teaching tools, to make their classrooms more attractive to the students. Now is another new era for teachers to learn about these new tools and methods to gain better control of the classroom and to increase students’ engagement and interactions.

SW: We hear quite a lot about how the COVID-19 context is contributing to heightened stress and anxiety for students. I know that each of you has been involved in student pastoral support. Please can you share with us what your university and college are doing to support their students’ well-being and enhance their mental health at this time?

HS: COVID-19 posed a huge challenge to universities. For example, more than 40,000 students at Peking University couldn’t return to the campus. Our staff in charge of student affairs had to make thousands of phone calls every day, to check on the students’ status and inform them of PKU’s

COVID-19 prevention measures and alternative modes of teaching. Our staff have been paying extra attention to students with mental health problems. For those students from families with financial difficulties, our staff sent them computers and mobile phones and purchased internet provision for them, to ensure they have no difficulty accessing internet.

Our university requires the tutors of all faculties and departments to have one-on-one communication with those students preparing for graduation, helping them with their studies, providing guidance on thesis writing, and defence. This year, we put additional efforts to offer more job opportunities and released over 100,000 job vacancies, which was a considerable increase to last year and ensured graduate employment rate this year was at the same level as previous years.

LR: We’ve had similar issues here in the U.K., and especially so at the start of the new academic year, when we have been so concerned to support our arriving first-year students as they settle into university life at such an unusual time. My role as Dean of an Oxford college means that my main responsibility is to make sure that the college environment is such that it promotes the health and well-being of all our students. So, my concern is not so much with their academic work—that’s the responsibility of some of my colleagues. Rather, my responsibility is with the students’ well-being, as well as dealing with their behavior, when it may be falling short of what we would like it to be.

So, I’ve been deeply involved in thinking about how we best prepare our college to keep our students, first of all, safe in terms of infection in line with all the government guidelines and our responsibilities to public health. But at the same time, how do we try to mitigate those restrictive circumstances somewhat, so that our students can feel as though they’re getting that really important experience of being at university? Because the schools in the U.K. have been closed since March, the majority of our first-year students were just so delighted to be here; to be back in full-time education was for them a huge thing.

Part of my role is helping the students to understand that their experience, although very different in some ways, isn’t different in other ways, despite the pandemic. Over the summer vacation, we worked very closely with our existing students to build a very strong network of support amongst the students themselves, and so we consulted with our undergraduates and postgraduates at every point, gaining their cooperation and their input into our planning. We have what is called “Peer Supporters” within each college, and these are fellow students to whom other students can turn as a kind of “first port of call” if they’re having any anxieties. We’ve also been much more proactive in reaching out to our students, asking them what difficulties they’re facing, asking how can we help with that, reassuring them that we’re here to help, and offering some practical solutions that we might be able to help them with, and pointing them towards other kinds of support that we can offer.

So, it’s a cooperative and collaborative effort that is ongoing at the moment, with weekly meetings among our pastoral support team. This term, we have been acutely conscious that we have students moving in and out of isolation, so are addressing ourselves to supporting them on a practical level, but also on an academic level—how to ensure they can carry on with their learning even though they may be isolating. We know very well that no one can separate their academic and personal lives, the two are absolutely connected. So, we put the systems in place to ensure that we can be alert much sooner to any academic issues that might be coming up and then think immediately about whether that might be connected to something else that’s going on, and vice versa.

SW: I am very glad to hear that so much collective effort has been going into supporting students’ pastoral needs, and of course our top priority is providing them with the best learning experience and enabling them to achieve the greatest outcome of their university study. At the same time, I don’t want to overlook the massive pressures accumulating on professors and teachers, on the education provider’s side. How has this pandemic impacted our own capacities—practical, physical, mental, and emotional? This is a wide and powerful topic, but one which I think has not been talked about very much.

HS: Since my own work setting is the Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning, we did not experience so much mental or emotional pressure ourselves. My understanding is that the greatest sense of pressure for our faculty members was how to teach online. For example, how to teach without a blackboard is a real challenge for faculties of the School of Mathematical Science. For them, how to write on a blackboard online, how to avoid the impact of network instability on the reasoning process, how to select a suitable network platform, or to avoid disturbance at home; these were their key concerns and worries. And they found very practical solutions; the faculty who are used to teaching with a blackboard decided to come to campus to record or live-stream online, facing the empty classroom, so that the students could watch the courses online at any time, anywhere.

LR: The experience of adapting to online teaching has definitely made me think about my own teaching practice, raising many reflections: Why do I teach the way I do, and can this move easily into an online format, or do I need to be thinking about changing that? I’m very conscious of how hard all my colleagues throughout the university have been working. We are all of us giving a huge amount of our time and effort to this, and here in the U.K., our government has changed its mind and direction many times. So, we have found ourselves putting a lot of plans in place, and then the next day they change their mind, and you have to revise and adjust. The support from my colleagues across the university and within the college has been absolutely vital to being able to keep going.

I have thought a lot about the fact that, as a teacher, we like to be in control of our space. We like to walk into a classroom or a lecture hall thinking, “I know my subject, I know what I’m going to say, I know how I’m going to say it,” and everything works as we anticipate. This time has made me realize that I’m not in control, I’m at the mercy of the internet suddenly going down, or the shared screen not working, or one of the students finding they can’t hear what I’m saying.

So, I’ve had to relinquish that sense of control to some extent and be much more open about sharing with my students that I’m uncertain about this, I’m not entirely sure how this is going to work, but we’re going to do this together and we’re going to work through it. I have felt increasingly tired as the months have gone past and have considered what effect that might be having on my effectiveness as a teacher, and even more as someone who is very much involved with the emotional and mental health of our students. We all know we can only be good teachers, effective teachers if we understand ourselves and this time has made me reflect a lot on that.

So how well is the institution looking after us? As teachers and as universities we are focused on our students, as absolutely we should be. But it is a valid question, how well is the institution set up to look after us, because we are in many ways its most valuable resource.

SW: Someday, the pandemic will walk away. And when that happens, do you think that teaching will return to what it was before COVID-19? Indeed, now that everyone has found that they can attend “university by zoom”, will we continue to need a physical university?

LR: One thing that has become very obvious during this pandemic is that, absolutely, we need universities. We need physical universities, and we need students in them. There’s a lot of scope for creativity, particularly when it comes to issues of inclusivity and diversity, and access, and we can and should use everything that we’ve learned during this time to think very seriously about how we go forward with that in our universities. But I have no doubt that we need physical universities. If there ever was any doubt, I think the pandemic has shown us how much universities are needed by our populations and our planet.

HS: I agree that we do need physical universities. We are embracing online teaching, and now the mission of university education is not only knowledge delivery, but also how to develop further and be ready for career development and personal life. So, in the education reform driven by technology, I think two issues should be addressed. First, talent training should go beyond disciplinary boundaries. For example, public health during the epidemic required not only talents in medicine but also in fields such as biology, communications, political science, international relations, engineering, and others. Second, teaching and learning platforms work best when they are conducive to delivering and sharing high-quality education resources. I think world-class universities such as Oxford will continue to take a leading role in the future.

JOIN SSIT

JOIN SSIT